Attention from the world has been brought to shine on the Duke of Buccleuch’s art collection in the last decade. First, when the Leonardo da Vinci painting was stolen in 2003 and recovered in 2007, and again in 2008 when a family portrait of Henry VIII and his children was discovered.

One of the principal homes of the Duke of Buccleuch*, Boughton House, located in Northamptonshire, contains artworks by a wide range of masters such as El Greco, Gainsbourgh, van Dyck and Rembrandt. Known as the ‘English Versailles,’ the House, set in an estate of over 10,000 acres, has “seven courtyards, 12 entrances, 52 chimney stacks and 365 windows” (“Boughton House”). The style of the rooms themselves are wonderfully preserved Baroque with treasures of furniture, tapestries and carpets—“within a few steps, you will see the finest French furniture from Boulle, enjoy beautiful Mortlake tapestries and 16th-century carpets from the Middle East” (“Boughton House”).

Besides Boughton House, the Duke of Buccleuch and Duke of Queensberry call Langholm, Bowhill and Drumlanrig home. There are “also about 850 high-value acres around Dalkeith Palace near Edinburgh” (Cohen). These homesteads make the “Buccleuch Property one of Europe’s largest private landlords” (“Our History”). When the 9th Duke of Buchleuch and 11th Duke of Queensberry died, it was claimed that if “laid end to end, the walls and fences that bounded his 280,000 acres would have stretched from Drumlanrig, his castle in Dumfriesshire, to San Francisco” (“The Duke of Buccleuch Obituary”).

The Duke explained what all was involved in managing the estates when he wrote in Country Living: “I run an enterprise involving more than 1,000 people, producing each year 127,000 sheep, 13,500 cattle, 18 million liters of milk, 20,000 tons of cereals and 50,000 tons of timber. At the same time I am responsible for 430 square miles of beautiful countryside and the people and wildlife it supports” (Roth). Included are “over 1,000 properties, 11,000 hectares of woodland, and 200 tenanted farms, all of which is looked after by some 350 employees” (“Our History”).

While acknowledging the vastness of his estates, the 9th Duke declared he was only worth £85m. A recent land survey placed the Dukedom’s 240,000 acres of land valued at £800m to £1b (Cohen). Upon the 9th Duke’s death, journalists guesstimated that the Buccleuch estates, which “run in an almost unbroken line across southern Scotland, were worth upwards of £300 million” (“The Duke of Buccleuch Obituary”). This figure was closer to the mark than the £85m declared by the Duke. When his Last Will and Testament was proven, it revealed a £320m fortune (“Buccleuch’s True Wealth Revealed as Will Discloses £320m Fortune”).

Collecting wealth through marriages matched family’s collection of names. Anne Scott married the Duke of Monmouth (an illegitimate son of Charles II and Lucy Walters) at which time he took the surname Scott and the couple was awarded the Dukedom of Buccleuch. Around 1810, the 3rd Duke married the heiress to the Dukes of Montagu and he also was granted the Douglas dukedom of Queensberry (Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage 176). At this time, the Duke of Buccleuch added the last names together to form the unhyphenated surname Montagu Douglas Scott that the family bears to this day.

In addition to the dukedoms, of which Buccleuch is the senior title, the following titles are also part of the heritage: Marquessate of Dumfriesshire, the Earldom of Drumlanrig and Sanquhar, the Viscountcy of Nith, Thortorwald and Ross and the Lordship of Kinmont, Midlebie and Dornock” (“The Duke of Buccleuch Obituary”). Titles usually include properties and the Buccleuchs combined these to create one of the greatest landowning families in Great Britain.

One of the United Kingdom’s finest private art collections is part of the holdings of the Buccleuch estate. Estimated to be “worth 400 million GBP, including masterpieces by Rembrandt and Holbein”, the collection is spread amongst the Duke’s houses (“Madanna Back to Buccleuch”). The Buccleuch family would spend the autumn in the 120 room castle at Drumlanrig amongst the Holbein and Rembrandt paintings. At the New Year the Buccleuchs moved to Bowhill, basically a 100 room hunting lodge situated in wooded country with portraits by Gainsborough, Reynolds and Van Dyck. In the spring, the 11,000 acre estate of Boughton was the family destination with art treasures by Van Dyck (“The Duke of Buccleuch Obituary”). One constant was the only Leonardo da Vinci painting held in private ownership, The Madonna of the Yarnwinder, estimated to be worth between £30 – £50m, that supposedly traveled with the 9th Duke on his progresses (“The Duke of Buccleuch Obituary”).

Shockingly, on 8 August 2003, two men posing as tourists overpowered a tour guide at Drumlanrig Castle in Dumfriesshire (in full view of security cameras and other visitors who took pictures on cell phones as the thieves exited) and made off with the da Vinci masterpiece without a trace. Experts speculated that the painting remained in Scotland as the notoriety of the work and the theft itself would have made it nearly impossible to sell on the black market. It was assumed that a specific individual or group organized the theft. Not recovered for four years, the speculation was correct: the painting had remained in Scotland.

Yarnwinder, by Leonardo da Vinci

Da Vinci is thought to have worked on the painting between 1499 and 1507 for Florimond Robertet, Secretary of State to King Louis XII of France (Kemp Leonardo da Vinci 218). The Buccleuch family has owned the painting for over 200 years. Although there are two versions of the painting (one in private ownership in New York), most believe the Buccleuch version is almost all done by Leonardo’s hand with some of the background accredited to his workshop (Penny 543).

We know of the painting because of two letters which survive from Frater Pietro Gavasetti de Novellara to Isabel d’Este in 1501. Isabel requested that Frater Pietro, who would be in Florence at the time Leonardo would be there, commission the artist, on her behalf, to create her portrait. De Novellara reported back to Isabel that Leonard’s “mathematical experiments have absorbed his thoughts so entirely that he cannot bear the sight of a paint-brush. But I endeavoured as skillfully as I could to inform him of Your Excellency’s wish” (“A Carmelite Link to Leonardo da Vinci”).

Frater Pietro related how Leonardo hoped to complete his engagement with the King of France at which point he “would rather serve Your Excellency than any other person in the world”(“A Carmelite Link to Leonardo da Vinci”). De Novellara cautioned that da Vinci had to finish “a little picture which he is painting for a certain Robertet, a favourite of the King of France.” The little picture which Leonardo was painting was a “Madonna, seated as if at work with her spindle, while the Child, … has taken up the winder, and looks attentively on the four rays in the shape of a cross, as if wishing for the cross, and holds it tight, laughing, and refusing to give it to His mother, who tries in vain to take it from Him” (“A Carmelite Link to Leonardo da Vinci”). The consensus by art historians is that this is the work of Leonardo, perhaps finished by artists in his workshop, which was delivered to Florimond Robertet. Surprisingly, the earliest documented owner is Marie Joseph duc d’Hostun de Laume-Tallard. How he acquired the work is unknown; his collection was diverse and came from many sources. d’Hostun’s “entire collection was dispersed in March 1756 at an auction in Paris” (Turner 274). Lady Elizabeth Montagu brought da Vinci’s The Madonna of the Yarnwinder to the Buccleuch family upon her marriage in 1767 to the 3rd Duke. She was heiress to her parents’ art collection and it is clear they purchased the work from d’Hostun in 1756. The masterpiece was “conclusively indentified as a work by the Renaissance master only in 1986 following scientific tests (“Raiders Steal £25m Leonardo Painting”).

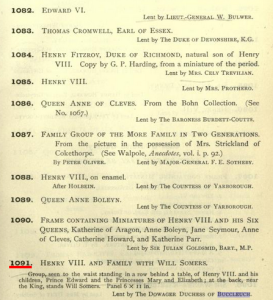

With The Madonna of the Yarnwinder safely returned, the next big event in the art collection of the Buccleuch estate was when Chris Lister, house manager at Boughton House, brought to the attention of Tracy Borman and Alison Weir “a never-before-exhibited picture” of Henry VIII and his family (“The Forgotten Portrait”). This blogger must dispute the claim that this painting has never been seen before. In fact, it was seen in The Tudor Exhibition at the New Gallery in 1890. Freeman O’Donoghue wrote a text, A Descriptive and Classified Catalogue of Portraits of Queen Elizabeth, in 1894, in which he gathered together information from “the catalogues of the exhibitions held from time to time in London, at which a large number of portraits of Queen Elizabeth have been shown” (O’Donoghue v). O’Donoghue offered special thanks to Sir George Scharf, Secretary and Director of the National Portrait Gallery for his help in assisting him [Freeman] by “generously allowing him unrestricted access to the sketches in which, during a long course of years, he has recorded all portraits of interest that came under his notice” (O’Donoghue v). O’Donoghue must also credit himself as he was thanked in the credits of the Exhibition of the Royal House of Tudor catalogue for his work. Therefore, it must be concluded that either Freeman or Sir George gained access to the Buccleuch collection and either informed the curators of the New Gallery or the painting was general known. Below is the exact entry from the Catalogue.

A recently re-discovered painting of Henry VIII and His Family.

Dowager Duchess of Buccleuch (Ditton Park Slough), In a picture of Henry VIII, his children, and Will Somers. King Henry, Prince Edward, and the Princesses Mary and Elizabeth stand in a row behind a table, the king on the left and Elizabeth on the right. Somers is behind, seen between the king and Prince Edward. Princess Elizabeth wears a hood, and plain dress with deep frills at the neck; her right hand is thrust into the front of her dress, (see Engravings, No, 3). Panel, 11 in, x 6 in. [Not a contemporary picture] No. 1091 of the Tudor Exhibition, 1890 (O’Donoghue 2).

Facsimile of A Descriptive and Classified Catalogue of Portraits of Queen Elizabeth.

Page from the catalogue of the Exhibition of the Royal House of Tudor which would have been the original source for O’Donoghue .

Interestingly enough, O’Donoghue acknowledged that “there are doubtless other pictures hidden away in country houses to which no clue could be obtained, but it is confidently believed that all the important examples are here recorded” (O’Donoghue 2). Consequently, it is understandable to accept that until 2008**, the painting was “normally in a private area of the house with a number of other Tudor portraits” (“Queen Elizabeth I’s Rare Portrait”). Unbeknownst to Lister, the exposure of this painting would create a frenzy of interest from Tudor scholars. Lister acknowledged that “we knew it was important because it’s a picture of Henry VIII and his family but we did not realise it in the context of Elizabeth as a princess” (“Lost Portrait of Elizabeth I as a Young Princess Found”). Remarkably, O’Donoghue recognized the importance of Elizabeth in the painting as she was allotted the lengthiest description by him in his Catalogue in 1894.

Shown in the painting are Henry VIII, his jester, Will Somers, his son the future Edward VI, and his daughters the future Queens Mary and Elizabeth I. Clear evidence of the artist and time-period is not available. Although most experts believe “it is a copy of an original panel painting, which is thought to date back to the early 1550s” (“Rare Portrait of Elizabeth I Found”). This copy was painted between 1650 and 1680.

With modern headlines and news articles touting this discovery as a lost portrait of Queen Elizabeth as a princess, it is easy to exclude the importance of all the other figures but understandable. Henry had plenty of depictions of him; Edward never reached adulthood so his countenance is similar to others done of him; and, Mary was an adult and looked similar in other images although having her likeness at this time of her life is intriguing. Elizabeth, as queen, was certainly painted enough times for viewers to identify her image readily. Elizabeth as a young adult is another story. According to the BBC “only two other paintings of Elizabeth before her accession to the throne are known to exist” (“Portrait of Princess Elizabeth I Found”).

The future Edward VI The future Mary I

Assigning an artist to the work is next to impossible, as is any attempt to attribute the original to anyone specific; although, speculation has recognized William Scrots as the l original artist. As for who commissioned the work, Will Somers is this blogger’s guess. Precedent had been set for including the jester in Tudor family portraits, but that would have been when Henry VIII was alive. For further discussion on the role of the fools in Tudor paintings, see the previous blog post on The Family of Henry VIII.

Will was a favorite and intimate of the Court. Kept in the establishments of all of Henry’s children, he certainly could have had the means and connections to authorize a group portrait. Alison Weir theorized this painting was done during the end of Edward VI’s reign because “the boy King is shown in the centre of the picture, and his figure is larger than those of his older sisters” (Weir). In technical terms it is not a flawless painting, but the importance comes from having the likenesses of the Tudor children at this time in their lives available so art historians can try to identify unknown works. A National Portrait Gallery painting, previously listed as Unknown Lady or as Lady Jane Grey, has caused second thoughts after comparison with the Boughton portrait. In the paintings, the sitters, “both wear almost identical costume; there are strong similarities in the jaw, mouth and nose…” (Weir). Was one of these derived from the other, and was this a “known portrait type of the princess” (Weir)? Other “inconclusive portraits at Syon House, Audley End and Berry Hill…” are also being considered “portraits of Elizabeth as a princess” (“’Lost Portrait of Elizabeth Found”). Obviously, the soberly-dressed young woman is completely different from the imagery of ‘Gloriana’ that dominated the majority of Elizabeth I’s reign.

Positively identified portraits of Elizabeth as a young girl are very rare. After her mother’s death, her life as a declared illegitimate daughter of King Henry was not one of prominence. Portraits of her would not have been a priority but to exclude her was not a politically suave move by Henry, or Edward once he ascended the throne. Elizabeth was a king’s daughter and, thus, she was important in the international marriage market. For Elizabeth to be used as political leverage in the power struggles of Europe, the individual kings would have to maintain her status and position within the family—this would explain her inclusion and her sister Mary’s in group portraits. It must be remembered that Elizabeth, while important as Henry’s daughter, was not a dynastic priority as emphasized in her placement in the group painting. Furthest from the seat of power as second in line to the throne, no one could have guessed that she would one day wear the crown.

*Originating from the 10th century, the name Buccleuch has been the object of much misspelling and poor pronunciation. According to the Debrett’s Peerage, it is pronounced ‘Buckloo.’ Legend has it “King Kenneth III was hunting in a deep ravine or ‘cleuch’ in the heart of the forest when a young buck became cornered and charged towards the unarmed King. A young man named John Scott seized the buck by the antlers and wrestled it to the ground, saving the King’s life. From that day, the Scott family were referred to as Buck Cleuch, the ‘buck from the ravine’, and were rewarded” (“Our History”).

**BBC History Magazine reported the complete findings in June 2008.

References

“Boughton House.” Boughton House. n. d. Web. 25 Jan. 2015. <http://www.boughtonhouse.co.uk/>.

“Buccleuch’s True Wealth Revealed as Will Discloses £320m Fortune.” The Scotsman. 12 Sept. 2007. The Scotsman on Sunday. Web. 25 Jan. 2015. <http://www.scotsman.com/news/scotland/top-stories/buccleuch-s-true-wealth-revealed-as-will-discloses-163-320m-fortune-1-1428191>.

“A Carmelite Link to Leonardo da Vinci.” The British Province of the Carmelite Friars. 26 Dec. 2011. British Province Bulletin Web. 2 Feb. 2015. <http://www.carmelite.org/index.php?nuc=news&func=view&item=640>.

Cohen, Tamara. “Blue-Blooded Britain: Who Owns What?” This Is Money. 10 Nov. 2010. The Daily Mail. Web. 25 Jan. 2015. <http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/mortgageshome/article-1707666/Blue-blooded-Britain-Who-owns-what.html>.

Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage, 1995. Ed. Charles Kidd and David Williamson. London: Debrett’s Peerage Limited and MacMillan Reference Books, 1995. Print.

Doran, Susan and Norman Jones. The Elizabethan World. London: Routledge, 2011. Print.

Doran, Susan. The Tudor Chronicles 1485-1603. New York: Metro Books, 2008. Print.

“The Duke of Buccleuch Obituary.” The Daily Telegraph. 5 Sept. 2007. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Web. 25 Jan. 2015. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1562180/The-Duke-of-Buccleuch.html>.

Exhibition of the Royal House of Tudor. Lord De L’Isle and Dudley, President, The New Gallery. London: The New Gallery, 1890. Internet Archive. Web. 16 Feb. 2015. <https://archive.org/details/exhibitionofroya00newgiala>.

“The Forgotten Portrait.” BBC Radio. 28 May 2007. bbc.co.uk/radio4. Web. 30 Jan. 2015. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/today/reports/arts/elizabeth_20080527.shtml>.

Ives, Eric. Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery. Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing, the John Wiley & Sons, 2009. Print.

Kemp, Martin. Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Google Books. Web. 1 Feb. 2015. <https://books.google.com/books?id=ZuLvRD16qWMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Leonardo+da+Vinci%E2%80%99s+Madonna+of+the+Yarnwinder:+A+Historical+and+Scientific+Detective+Story&hl=en&sa=X&ei=Nz3OVOyMEcuvggSq_YOADA&ved=0CFQQ6AEwCA#v=onepage&q=yarnwinder&f=false>.

“Lost Portrait of Elizabeth I as a Young Princess Found” The Yorkshire Post 27 May 2008. Web. 3 Nov. 2014. <http://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/main-topics/local-stories/lost-portrait-of-elizabeth-i-as-a-young-princess-found-1-2502362>

“Madonna Back to Buccleuch.” Clipped News. 5 Oct. 2007. Web. 25 Jan. 2015. <https://clippednews.wordpress.com/2007/10/05/madonna-back-to-buccleuch/>.

O’Donoghue, Freeman M. A Descriptive and Classified Catalogue of Portraits of Queen Elizabeth. London: Bernard Quaritch, 1894. Internet Archive. Web. 16 Feb. 2015.

“Our History.” Buccleuch Property. 2005. Web. 25 Jan. 2015. <http://www.buccleuchproperty.com/wp-buccleuch/>.

Penny, Nicholas. “Leonardo’s Madonna of the Yarnwinder.” The Burlington Magazine 134.1073 (1992): 542-544. JSTOR. Web. 1 Feb. 2015. <http://www.jstor.org.lhezproxy.d128.org/stable/885186?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoAdvancedSearch%3Fc3%3DAND%26amp%3Bf0%3Dall%26amp%3Bpt%3D%26amp%3Bc1%3DAND%26amp%3Bisbn%3D%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bq4%3D%26amp%3Bla%3D%26amp%3Bq3%3D%26amp%3Bf6%3Dall%26amp%3Bq5%3D%26amp%3Bf3%3Dall%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bc5%3DAND%26amp%3Bf5%3Dall%26amp%3Bc6%3DAND%26amp%3Bq6%3D%26amp%3Bf1%3Dall%26amp%3Bq0%3Dmartin%2Bkemp%26amp%3Bf2%3Dall%26amp%3Bed%3D%26amp%3Bc2%3DAND%26amp%3Bq2%3D%26amp%3Bq1%3Dyarnwinder%26amp%3Bsd%3D%26amp%3Bf4%3Dall%26amp%3Bc4%3DAND&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents>.

Perry, Gillian. Gender and Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, The Open University Google Books. Web. 11 Nov. 2014. <http://books.google.com/books?id=LIARJjg8w_gC&pg=PA46&lpg=PA46&dq=Guicciardini+teerlinc&source=bl&ots=7H6F2VAVCz&sig=J2GWwtwkFMB2bjNudlYQWT1CNaM&hl=en&sa=X&ei=uhliVOWPMMuZyAS9i4HgDQ&ved=0CDAQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=Guicciardini%20teerlinc&f=false>.

“Portrait of Princess Elizabeth I Found. United Press International. 28 May 2008. upi.com/Entertainment_News. Web. 2 Nov. 2014. <http://www.upi.com/Entertainment_News/2008/05/27/Portrait-of-Princess-Elizabeth-I-found/UPI-12901211931592/>.

“Queen Elizabeth I’s Rare Portrait.” FemaleFirst. 28 May 2008. femalefirst.co.uk. Web. 3 Nov. 2014. <http://www.femalefirst.co.uk/royal_family/Queen+Latifah-51331.html>.

“Raiders Steal £25m Leonardo Painting.” The Daily Mail. 28 Aug. 2003. Web. 29 Jan. 2015. <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-193966/Raiders-steal-25m-Leonardo-painting.html>.

“Rare Elizabeth I Portrait Found.” BBC News. 28 May 2007. news.bbc.co.uk. Web. 30 Jan. 2015. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/northamptonshire/7421051.stm>.

Roberts, William. Memorials of Christie’s: A Record of Art Sales from 1766 to 1896, Volume 1. London: George Bell & Sons, 1897. Google Books. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Somerset, Anne. Elizabeth I. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. Print.

“Tallard, Camille, marquis de la Baume-d’Hostun, baron d’Arlanc, comte de.“The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.. 2014. Encyclopedia.com. Web. 1 Feb. 2015. <http://www.encyclopedia.com>.

Tinning, William. “Police Seize £30m Stolen da Vinci in Law Firm Raid.” The Herald Scotland. 5 Oct. 2007. Web. 1 Feb. 2015. <http://www.heraldscotland.com/police-seize-pound-30m-stolen-da-vinci-in-law-firm-raid-1.866566>.

Turner, Jane. The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 30. New York: Grove, 1996. Print.

Weir, Alison. “Two Newly Discovered Portraits of Elizabeth I as Princess.” Alison Weir. Alison Weir, n.d. Web. 14 Aug. 2014. <http://alisonweir.org.uk/books/bookpages/more-children-of-england.asp>.

Alison Weir, Anne Boleyn, Anne Somerset, Audley End,Berry Hill, Boughton House, British History,Charles V Holy Roman Emperor, Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage,Drumlanrig, Duke of Buccleuch, Duke of Queensberry,Dumfriesshire, Earl of Drumlanrig, Elizabeth I,Elizabeth Montagu,Elizabeth Regina,Elizabethan,Elizabethan England,English History,ENglish Versailles, Eric Ives, Florimond Robertet, Frater Pietro Gavasetti de novellara,Gillian Perry, Henry VIII, Isabel d’Este,Langholm, Leonardo da Vinci, Lord of Dornock, Lord of Kinmont, Lord of Midlebie, Marie Joseph duc d’Hostun de Laume-Tallard,Montague Douglas Scott, Queen Elizabeth,Queen Mary, Spanish Ambassador, Susan Doran, Syon House,Tamara Cohen, The Family of Henry VIII,The Madanna of the Yarnwinder, Tudor,Tudor Court, Tudor Dynasty, Tudor History, Will Somers,William Scrots