The Portrait

The Family of Henry VIII, created by an unknown artist around 1544-1545 and on display now at Hampton Court in the Haunted Gallery, was basically a dynastic propaganda device. Apart from Queen Jane Seymour, who would have been dead for close to a decade, “the figures appear to have been painted from life” (Thurley 214). An enthroned Henry is front and center surrounded by his children and Jane, his third wife.

The Family of Henry VIII

Now at Hampton Court Palace, c. 1545

Painted by an unknown artist, Oil on canvas, 141 x 355 cm

Left to Right: ‘Mother Jak’, Lady Mary, Prince Edward, Henry VIII, Jane Seymour,

Lady Elizabeth and Will Somers

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth I

Henry VIII, fashioned in a similar pose to the Whitehall mural (depicting himself, his father and mother and Jane), the “super confidence of the mural has been replaced by the image of the elder statesman with his dynasty secured before him, and, unlike the mural, it is a picture of the future as well as of the present” (Lloyd 37).

Prince Edward stands to the King’s right and beyond the columns stands Lady Mary on the far left and the Lady Elizabeth on the far right. Susan Doran speculates that The Family of Henry VIII “was probably painted to commemorate the 1544 statute that restored the bastardized Mary and Elizabeth to a place in the succession” (Doran The Tudor Chronicles 1485-1603 195). An interesting theory considering that the princesses were beyond clear lines of demarcation in the form of the columns, giving the impression that the true family unit was Henry, his legitimate heir and the boy’s deceased mother. Including Mary and Elizabeth could be a message of acceptance, yet this blogger still wonders if the distance was to show their classification of illegitimacy and their obvious secondary role as, the King’s “two daughters stand in the wings in reserve” (Lloyd 37).

Through the open doorways on either side of the princesses, figures of royal servants can be seen. The woman is likely Jane, Princess Mary’s resident fool, and the man, “Henry’s jester, Will Somers, who is wearing the livery of the royal household” (Doran The Tudor Chronicles 1485-1603 195). The painting was probably completed for “the presence chamber at Whitehall, where it is known to have been hanging in 1586-1587” as the interior and exteriors appear to be of that palace (Weir Henry VIII The King and His Court 473). This painting was first recorded in the Works Accounts according to Howard Colvin in his book, The History of the King’s Works. Colvin quoted a source identifying, “a greate table containing Kinge Henrie, Prince Edwarde and the ii ladies his daughters Pictuors’” (Strong 49).

The composition is dominated by the four columns in the foreground which create a “distinct frame through which the whole composition is viewed” (Rawlinson 110). King Henry becomes the focal point because “these columns also create a three-dimensional space (or centre of perspective)…” (Rawlinson 110). Included in the act of framing, are the two columns in the mid-ground. All of the columns act to divide the composition into five areas: “the central bay occupied by Henry VIII, Prince Edward and Jane Seymour; the two bays immediately adjacent occupied by Princesses Mary and Elizabeth; and the outer pair of bays, only partially shown, through the doorways of which a final pair of figures are glimpsed…” (Rawlinson 110). Therefore, a geometric pattern is fundamental to the entire work. In fact, according to Rawlinson, the entire layout reflects the “architectural diagrams in Henry VIII’s Geometria”* (Rawlinson 110).

Dating the work is difficult; it would be logical to assume, with Geometria published in perhaps 1541 and the painting was truly influenced by that work, to have been created after that year. If the Raphael designed tapestry, “The Healing of the Lame Man” acquired by Henry in 1540-1542 (more on that later), was used as a guide, a date of the mid 1540s would be plausible. Although Henry appears Holbeinesque, and the piece owes a “debt to the great wall-painting in the Privy Chamber of Whitehall Palace by Holbein”, this would have been done after the master’s death in 1543 (Strong 49). Using the age of Prince Edward as a clue it would appear around 1545 when he was eight or so.

Often portraits are dated using evidence from the clothing depicted in them. In this case it would be not be very reliable as the clothing differed between the girls and the queen. Jane was “dressed in almost the exact costume depicted in the copy of Holbein’s original fresco, dating 1537” (Norris 287). Queen Jane wore “bodice, sleeves, skirt, and train of gold brocade, the sleeves lined and turned back with ermine; the underskirt and false sleeves are of crimson velvet.” In her hand she holds “either a pomander or a reliquary of gold, set with a large emerald, and attached to the end of the girdle” (Norris 288). The princesses both wore “French hoods” (Shafe) and were dressed alike. Their gowns are of “slate-coloured damask, the skirts, mounted over Spanish farthingales, having very long trains after the English fashion.” A deep red velvet was used to fashion the under-skirts and false sleeves of their gowns. One difference was in the sleeves: the “sleeves, worn by the Princess Mary, are turned back with a lining of the same damask; but the Princess Elizabeth’s sleeves are lined and turned back with grey fur” (Norris 288).

Another difference between the two princesses lies in their jewelry, notably their necklaces. Catholic Mary wore a cross while a necklace of emerald and pearl with the initial “A” adorned Princess Elizabeth’s neck. As noted in a previous blog, Elizabeth Regina: Her Mother’s Memory at https://elizregina.com/2014/01/20/elizabeth-regina-her-mothers-memory/, many experts claim this was an ornament Elizabeth inherited from Anne Boleyn. Would Henry have allowed the jewelry to be worn? Did Elizabeth wear it to defy and perhaps infuriate her father (see the blog, “The Fourth Step-Mother of Elizabeth, Katherine Parr” at https://elizregina.com/2013/06/04/the-fourth-step-mother-of-elizabeth-katherine-parr/) enough to banish her from Court? Perhaps Henry allowed Elizabeth to display the necklace to honor her mother. Or as his way to send a message wanting people to associate the girl with her mother and her illegitimacy in contrast to the legitimate heir, Edward, seated next to him.

Princesses Mary and Elizabeth

If this dynastic message was indeed Henry’s intention it appears as if “Henry had learnt to use art and portraiture in a less literal, more symbolic way by the end of his reign. It is usually read as a statement about Henry’s rapprochement with all three of his children at the end of his reign, and his inclusion of all three in the succession” (Doleman 121).

An interesting point is brought up by Brett Doleman. He speculates that the painting, with its strong emphasis on Edward and Jane, lends itself to the idea that someone in the Seymour clan had commissioned the work. Others reason that it was “made up for the sentimental satisfaction of the new King, Edward VI” (Norris 287). Regardless of who commissioned the work, its intent and purpose was to communicate the continuation of the Tudor dynasty.

Princess Elizabeth cropped from The Family of Henry VIII she was about age 12.

Dynastically the composition is obvious with Edward and his father dominating the view. Less obvious is the artist. No attribution has ever been proven although there have been several suggestions. Because of the age of Edward and the inclusion of his mother, one historian proposed the artist would be Edward’s “Court painter, Gwillim Stretes” (Norris 287). Another suggestion is that the “picture is the work of one of the Italians in the King’s service” (Strong 49). Art historian, Roy Strong, surmises an Italian source because The Family of Henry VIII “is remarkable as the earliest evidence that we have of any response in England to Raphael’s Acts of the Apostles tapestries…. The Healing of the Lame Man, with its extraordinary division of the surface into three distinct sections by the placing of the twisted vine columns of Old St. Peter’s, must be the source for the compositional structure of this Tudor family group” (Strong 49).

Architectural Influence:

King Henry VIII and his family are grouped “in an idealized setting defined by architectural order and controlled magnificence…” within a “real garden against the asymmetric forms and vernacular materials of real buildings. The Family of Henry VIII appears, in summary, to have been conceived as much as an architectural image, as it was a group portrait” (Rawlinson 110). The viewer, it is assumed, is not only familiar with the subjects but also with “architectural imagery as both as a liberal means of representing buildings and as a vehicle for abstract cultural or political discourse” (Rawlinson 111).

“The basic composition and architectural setting of The Family of Henry VIII appears to be original. In turn, Raphael’s design for the tapestry The Healing of the Lame Man has been adduced as a potential source for the colonnaded architectural setting”( Rawlinson 109). “The status of the architectural setting of The Family of Henry VIII is expressed by the comparatively small scale of the royal figures who inhabit its tall, colonnaded gallery” (Rawlinson 110). The prevalence of the architectural details causes a viewer to wonder whether or not the architecture of the building depicted in this painting is truly an historical palace. Roy Strong has determined that this painting is “a topographical record rare at this period” of the grounds and buildings of Whitehall Palace (Strong 85).

Strong also contends that the gallery depicted in the painting is of the palace’s interior décor. The setting for The Family of Henry VIII is “on the ground floor of the king’s lodgings at Whitehall Palace, and very probably represents a real interior set up for the portrait. (Thurley 214). Other experts disagree claiming the interior with its use of perspective and classical design “is more probably a fictive or idealized architectural space” (Rawlinson 110). Most likely, it is a combination of the two—a reflection of Whitehall and a more exaggerated view within the artist’s imagination to more clearly express the meaning he was trying to convey of the palace’s opulence and splendor.

What is agreed is that the “background of The Family of Henry VIII shows a view from Whitehall Palace northwards” (Lloyd 36). “A projecting wing of the palace with its painting can be seen in the background” (Thurley 212). And through the “two open arched doorways to either reside of the dais can be seen tantalising glimpses of the Great Garden of Whitehall with the King’s Beasts mounted on columns, and in the background the Lady Mary’s lodging with its grotesque decoration …” (Weir Henry VIII The King and His Court 473).

Most palaces interior decorations have been lost due to remodeling, etc., but some of what we assume is Whitehall’s interior and can be seen in this painting. Although one historian believed that the “same gorgeousness and splendour distinguished all the King’s palaces”, this interior was most likely “Hampton Court which surpassed them all” (Law 238). Visible is “a richly decorated battened ceiling, wall paneling and pillars embellished with antique grotesque work, a painted floor, and an embroidered cloth of estate” (Weir Henry VIII The King and His Court 473). In fact, The Family of Henry VIII is viewed as a “crucial document in the study of early Tudor style and interiors” (Thurley 214).

Simon Thurley provided a thorough description of the portions of Whitehall Palace depicted in the painting. “The view through the archways show the privy garden in the south, with its low rails and beasts on poles. The left-hand archway shows part of Princess Mary’s lodging painted externally with grotesques. Through the right-hand archway part of the parkside can be seen, including a turret of the great close tennis-play. The floor of the room is plastered and painted, but the king’s chair stands on a rug. The canopy is a single piece of embroidery suspended from the ceiling. The ceiling is divided up by battens into squares, each with a royal badge. The paneling and pillars are carved with grotesques and highlighted with gold” (Thurley 214).

The free-standing columns with the arches behind which “open out onto two exact topographical views of the recently planted Great Garden of Whitehall Palace, a fact which would support the view that the architecture in which they stand must be a record of its interior decoration carried out during the 1530s” (Strong 49).

Healing of the Lame Man:

What inspiration encouraged the stunning architecture of the royal palaces, which in turn inspired the composition of the painting, The Family of Henry VIII? Many art historians credit Raphael’s masterpiece cartoons used for the tapestries in the Sistine Chapel.

Tapestry: Healing of the Lame Man by Raphael’s Cartoon

Pope Leo X determined that the Sistine Chapel should have tapestries that would be displayed on feast days below the masterpiece paintings by Michelangelo. Raphael was commissioned by the Pope to create cartoons for the tapestries and the artist decided “to fill the lower part of the lateral walls with ten subjects taken from the lives of the apostles Peter and Paul and from that of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr” (Passavant 256). Raphael designed to recite on one side the history of St. Paul, and on the other side that of St. Peter; and these “histories were to fill up the compartments of the wall, five on each side from the entrance to the altar” (Killikelly 110). Known as the Acts of the Apostles, this series of cartoons became famous in its own right and the tapestries, “woven with silk and gold and silver threads, may still be seen in one of the galleries in the Vatican” (Scharf 265). Johan Wolfgang Goethe remarked that the “tapestries are the only works of Raphael that do not look small after one has seen the frescoes of Michael Angelo in the Sistine Chapel” (Killikelly 110).

Woven tapestries require a different type of composition than paintings in order to be properly showcased. There must be more movement and architectural interests rather than the typical expressive human form. Eugene Muntz opined that Raphael committed a mistake because “he conceived these cartoons in exactly the same spirit as those which he had been accustomed to make for execution in fresco, without taking account of the difference in materials and destination” (Muntz 371).

Sympathy was granted to the tapestry weavers who, according to M. Charles Blane, “in the presence of these sublime cartoons, were compelled to abdicate all the independence of their own skill to imitate respectfully the models of a great painter, and to render, as faithfully as the roughness and hardness of their material would allow, the noble character of his figures, the deep expressiveness of his heads, the pictorial force resulting sometimes from single strokes of the brush” (Muntz 458). Raphael left some freedom to the weavers on the basis of color and “was neither shocked nor surprised to find a yellow where he had put a red” (Muntz 458).

Each cartoon is “about twelve feet in height and from fourteen to eighteen feet in length. They were drawn on cardboard in chalk, tinted in distemper” (Killikelly 109). Opinions on how much of the cartoons were done by Raphael as opposed to his students changes with the vicissitudes of research. An accepted view was that it was not the custom of Renaissance master artists to perform the “drudgery personally” and to believe that “the cartoons were painted entirely, or even in large part, by Raphael’s own hand is extremely improbable” (Hunter “The Story and Texture Interest of Tapestries” 611). The Healing of the Lame Man, it is believed, was mostly done “by Giulio Romano …with the head of the second beggar …from Raphael’s own hand” (Passavant 261). This particular cartoon excels “all the rest of the series in its suitability for interpretation in tapestry. But this decorative fitness was not obtained by any neglect of dramatic qualities” (Muntz 380).

Regardless of the opinioned suitability of the cartoons, they are considered some of the greatest art treasures of the Renaissance. Quatre de Quincy does not hesitate to give them as Raphael’s masterpiece. “In these cartoons he indeed rises above himself. The collection of these memorable works out to be here pronounced what in truth it is, the climax, not only of the productions of Raffaello, but of all those of modern genius in painting” (Passavant 168).

The tapestries arrived from Flanders to the Sistine Chapel in Rome in 1519, “only a few months before the death of Raphael, and were hung up …on the feast of St. Stephen [December 16th] in the same year” (Passavant 167). Greeted with great enthusiasm, Giorgio Vasari, famous for his critical text, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, said the tapestries “seem rather to have been performed by miracle than by the aid of man” (Passavant 167).

Who worked this miracle? Were these treasures “woven at Arras by Flemish workmen” unknown to us (Scharf 263)? Luckily, a “notarial act, dated 14 June, 1532, informs us that Peter Aelst wove both the Acts of the Apostles and the Scenes from the Life of Christ” (Munz 374). Peter Van Aelst “during the whole of the first third of the sixteenth century, was incontestably the chief of the Brussels tapestry weavers. Leo X also designated him tapestry worker to the papal court…” (Munz 374).

As pointed out previously, the tapestries are obviously seen as an artistic treasure, yet the cartoons Raphael produced as the templates were seen as the culmination “of modern genius in painting” (Passavant 168). Curiously, once the cartoons served their purpose, they “were allowed to remain in neglect at Arras, till King Charles I, at the suggestion of Rubens purchased them to serve as patterns for a new manufactory of Tapestry which he was interested in encouraging at Mortlake” (Scharf 263).

The above sentence packs a great deal of information and generates equal amounts of speculation. As is known, Raphael’s cartoons for the Sistine Chapel’s tapestries were sent to Arras in present-day Belgium to be manufactured. Once the tapestries were safely delivered to Rome (where they have not had an undisturbed existence), the cartoons were ignored. Could an artist such as Raphael so undervalue his work that he would abandon it? Much speculation remains as to whether or not Raphael sold the Pope the cartoons outright or simply the right to use them.

Mystery surrounds the fates of all the cartoons. Pope Leo apparently forgot all about their existence (or value) and although most evidence suggests they remained in Brussels, other documents proclaim that several managed to surface throughout Europe and finally in Genoa. Therefore, in some quotes that follow, Brussels will be stated as the location of the purchase but it is accepted now that “the most magnificent works in the field of cartoon painting—Raphael’s cartoons for the tapestry cycle The Acts of the Apostles—were preserved in that city” (“Liechtenstein: The Princely Collections” 339). In a footnote to Passavant’s text, we learn that “five cartoons which had already disappeared in the time of Rubens, are still in existence in a church in France” (Passavant 167). Supposedly, Peter Paul Rubens “discovered the seven remaining cartoons at Brussels. Struck by their beauty, he advised Charles I to purchase them” (Muntz 377). Charles, at that time actually Prince of Wales, purchased them for a considerable sum of money. When Oliver Cromwell emerged in power in England, he ordered an inventory of royal goods in order to begin selling the property. The “Parliamentary Commissioners, in assessing the effects belonging to the Crown, valued the Raphael Cartoons at £300**, and in the sale catalogue they are entered as being ‘now in the use of the Lord Protector’” (Thomson 213). Cromwell did not sell the tapestries or cartoons. “For reasons which are still unclear, Oliver Cromwell did not sell the cartoons. Perhaps, given their modest purchase price, he did not think it worthwhile to sell them. It is also possible that he intended to commission another set of tapestries for himself” (“The Raphael Cartoons”).

Controversially, Vera Campbell believes the reason for the papal neglect of the cartoons was because Pope Leo had another set of cartoons executed based on the Sistine Chapel tapestries. “Not having Raphael’s original designs, of which he had only bought the right of reproduction, he commissioned Tomaso Vincidor di Bologna, a pupil of Raphael, to make designs from the Vatican tapestries…” (Campbell, Vera 106). “In a book found in Lisbon written on the life of Raphael d’Urbino, a passage on page 83 says ‘After the death of Raphael, Pope Leo X, sent Tomaso Vincidor di Bologna to Flanders in 1520 to order basselis tapestries as a present to Henry VIII’” (Campbell, Vera 106). These tapestries eventually emerged in the Berlin Museum as confirmed by Muntz in his Cartons de Raphael, and “agree in all details with the Kensington cartoons, between which and the Vatican tapestries there are serious discrepancies” (Campbell, Vera 106).

Therefore, Rubens found these cartoons which had been used to create the tapestries for Henry VIII, interesting points and ones this blogger cannot dispute one way or the other. What does remain factual is that seven cartoons, similar to the Sistine Chapel tapestries, are in possession of the United Kingdom. Regardless of whether the cartoons are the original works Raphael generated for Pope Leo or ones done by his students, they “retain much of their early beauty and form one of the proudest possessions of the English capital” (Muntz 377).

The cartoons, when purchased by Charles, were not in single sheets. In order for the weavers to handle the necessary materials, the cartoons were cut down into strips about a yard wide. The cartoons remained in their fragmented pieces until the reign of William III. Under William’s direction, the separate strips were “carefully pieced together and affixed to canvas” (Muntz 377). The masterpieces remained “in a lumber room at Whitehall, until William III commissioned Sir Christopher Wren to erect a room for them at Hampton Court” (Campbell, Vera 106). The cartoons remained there until “Queen Victoria allowed them to be removed to the South Kensington Museum” (Passavant 261).

Most experts agree that many rich patrons could have obtained reproductions of the tapestries as the cartoons were available in Brussels. It is estimated that there are “55 complete or partial sets of the tapestries known to have been made from the Raphael Cartoons” (Breeze). Included would be those tapestries dated from the 16th century that are or had been displayed in museums in Berlin, Madrid and Paris and those tapestries “made at Mortlake for Charles I now in the Garde-Meuble National [Paris]” (Muntz 386). Confusion over the whereabouts of many sets of tapestries emerges because of the the lack of precise records and excellent quality of the later productions specifically at Mortlake. “Probably the best monument to the Mortlake tapestry works is the set of Acts of the Apostles, after Raphael preserved in the French National Collection”. Identified by the “Car. Re. reg. Mortl., which unabbreviated reads Carolo rege regnant Mortlake, and means At Mortlake in the reign of King Charles” (Hunter Tapestries, Their Origin, History and Renaissance 119).

Mortlake, a residence on the River Thames in Surrey, “was adapted by Sir Francis Crane for the Royal tapestry works, where, … hangings of beautiful workmanship were executed under the eye of Francis Cleyne, a ‘limner,’ who was brought over from Flanders to undertake the designs” (“Sir Franics Crane English Tapestries”). Cleyne, or Clein, wove the Mortlake tapestries and his friend, “Edward Norgate commented on Clein’s ‘almost incredible diligence’ in the demanding task of accurately reproducing Raphael’s seven cartoons” (Campbell, “Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor” 188). A loyal and productive employee, Clein continued at Mortlake even after “Sir Francis Crane died in 1636 and the establishment became known as ‘The King’s Works’” (“Sir Franics Crane English Tapestries”).

Thomas Campbell, using an inventory taken by Anthony Denny, Keeper of Westminster Palace in 1542, cites textiles and tapestries “which included two pieces ‘of Arras of the history of Thacts of thapostles’ and another two ‘of hangings of Arras of thistory of Antiques’. No mention is made of any other Acts of the Apostles or Antiques tapestries in the inventory itself” (Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 73). However, notes in the inventory additions that “comprised several sets of tapestry including ‘Italinate of hangings of arras of thacts of the appostells lined thorough with canvas’ and ‘fyve peces of hangings of Arras wrought with Antiques lined throughout with canvas’. A marginal note records that these twelve pieces were purchased from John Baptist Gualteroti, merchant of Florence, in June 1542” (Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 73).

Identification of the palace where these tapestries would be hung cannot be made with certainty. Based on the date of their arrival and the remodeling and refurbishing of Westminster with the addition of the Banqueting House, one can “conjecture that the commissioning of these sets was linked with the modernisation which was taking place at Westminster in the early 1540s” (Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 78).

Accountability for the Henry VIII tapestries disappears for close to a hundred years and the next mention of the Acts of the Apostles only generates more confusion; is the discussion dealing with the 16th century tapestries or those created for Charles I at Mortlake? Campbell does give archival evidence of a warrant from July 19, 1628, to the keeper of the standing wardrobe at the Tower of London. The order was to “deliver to Sir Franices Crane, ‘A peece of Hangings of ye story of Acts of ye Ap[ost]les’” suggesting that examples were needed from Henry VIII’s set to construct Charles I’s (Campbell “Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor” 177). “New border designs for the first set were commissioned from an artist called Frans Kleyn, a native of Rostock, who had worked at the court of Christian IV in Copenhagen, before entering the service of the Prince of Wales in 1623-24. In 1626 Franics Clein, as he came to be known in England, was appointed official designer at the Mortlake tapestry…” (Campbell Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor 75).

After the Restoration, the cartoons were reassembled in the Royal Collection. As noted earlier, they became appreciated as works of art and displayed in Hampton Court. “During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the cartoons came to be regarded as some of the most important works of art in existence” (“The Raphael Cartoons”). Allowed on loan for an exhibit at the British Institute and for study by art students, the cartoons’ popularity increased. “When the National Gallery was founded in 1824, a number of artists lobbied for their transfer to the Gallery. Instead, in 1865 Queen Victoria sent them on loan to the South Kensington Museum” making the treasures available to a much wider audience (“The Raphael Cartoons”).

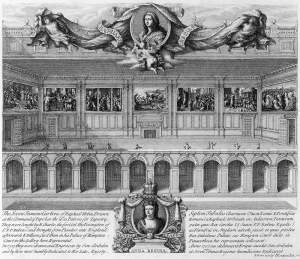

Image from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The cartoons installed at Hampton Court in ‘The Seven Famous Cartons[sic] of Raphael Urbin’, by Simon Gribelin, 1720. Museum no. Dyce.2504, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. (“The Raphael Cartoons”)

| The Acts of Apostles – CartoonsThe cartoons’ journey from creation by Raphael, to the Brussels workshop of weaver Pieter van Aelst to the Victoria and Albert Museum was complicated.Sometime after Henry VIII’s tapestries were completed (if indeed his were based on Raphael’s works and not copies), the cartoons appear to have passed into the hands of the Brussels merchant Jan van Tieghem (Campbell, Thomas 201). | The Acts of Apostles –TapestriesMost sources agree that the Henry VIII tapestry set was “woven from the same cartoons as those used for the papal set” and not from copies (Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 75). Although it is known that “numerous sets of Tapestries from these designs of Raphael were executed in England, and in all probability chiefly at Mortlake” (Scharf 264) from the “working cartoons painted by Francis Cleyns’ designs” (Campbell “Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor” 201-202). |

| Once in sold from Brussels, the next owner, according to Marcantonio Michiel, appears to be “Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga who bequeathed them to Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga of Mantua” (Campbell, Vera 103). | After purchasing the Raphael cartoons, King Charles I of England had a set of tapestries woven for himself. Having the Henrican and Stuart copies creates confusion. The purpose here is to follow the 16th century set as summarized by Thomas Campbell based on the scholarship of John Shearman.Following the execution of Charles I, two divergent stories emerge. One that “Oliver Cromwell held onto the King’s tapestries while selling his pictures. He hung the Acts of the Apostles in the State Rooms at Hampton Court” (Peck 82).Thomas Campbell proclaims the tapestry set was eventually “sold in October 1650 to Robert Houghton, leader of one of the fourteen syndicates which acquired large numbers of works of art from the sale of royal goods” (Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 70). |

| In 1623 at the urging of Peter Paul Rubens, Charles, Prince of Wales, purchased seven of the original Raphael cartoons, lacking their borders, from an unknown Genoese source (Delmarcel 142). | The tapestries left England when sold for £3,599 to the Spanish ambassador to London, Don Alonso de Cảrdenas, who was acting on behalf of Dom Luis Mẻndez de Haro, Marquẻs del Carpio.By 1662, the set passed into the collection of the Duke of Alba where it remained for over a hundred and fifty years. (Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 70). |

| As king, Charles I started the tapestry manufactory at Mortlake. He used the cartoons to complete a set of tapestries of The Acts of the Apostles for himself.“In a slit deal wooden case, some two cartoons of Raphael Urbin’s for hangings to be made by, and the other five are, by the King’s appointment delivered to Mr. Franciscus Cleane, at Mortlack, to make hangings by” (Scharf 264).Many other tapestry sets were created (some sources believe they were done on copies of the cartoons) and after sometime, Charles housed the cartoons in boxes at the Banqueting House. | The British Consul in Catalonia, Mr. Tupper, purchased the tapestries in 1823 and brought them to England.(Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 70). |

| After Charles I was executed, Oliver Cromwell preceded to sell off many of the royal collection. Surprisingly, it was noted at the time of his inventory that the cartoons are ‘now in the use of the Lord Protector’” (Thomson 213). He kept them. | Tupper exhibited the tapestries before they were acquired, in 1844, for the Kaiser Frederick Museum in Berlin under Frederick William IV of Prussia (Campbell and Cleland 108). |

| William III recognized the artistic treasure that he had and paid Sir Christopher Wren to build a special gallery at Hampton Court to showcase the cartoons. | Ironically, during the British invasion of Germany in 1945, the Expeditionary Force destroyed the English treasure. |

| In 1865, Queen Victoria loaned the cartoons permanently to the South Kensington Museum, now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum. | Historically, as written in mid-nineteenth century, it has been accepted that the tapestry set woven for King Henry VIII of England is “the very fine series of Tapestries now in the Public Museum at Berlin” (Scharf 265).This clarifies the difference between the Tudor and Stuart tapestry sets as mentioned above. With solid proof that the set last displayed in the Berlin museum was made for Henry VIII, the set in the possession of the French Louvre was the one created for Charles I. The Louvre set “bears the Royal English Arms … was later acquired by Mazarin, and was in Louis XIV’s inventory” (Digby 295). |

To return to the issue concerning the inspiration for the Tudor painting, let us examine the Renaissance manifestation of the Biblical story. In the parable depicted in this segment of the Acts of the Apostles, The Healing of the Lame Man, the apostles St. Peter and St. John come upon a lame beggar lying beneath the peristyle, a columned porch, at the Temple. Rather than give alms, St. Peter told the man that he would give “such as I have to give thee: in the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, rise up and walk” (Passavant 167). The lame man stood up and walked. Raphael places the scene of the miracle in “a three-aisled pillared gallery with a door in the background above which lights burn” (Delmarcel 144). Decorated columns “appear to have been copied from those still in the Basilica of St. Peter” at the altar in the chapel of the Holy Sacrament (Passavant 258). These columns “according to tradition had been brought from the Temple in Jerusalem” (Muntz 380). Bernini would later copy these “fluted Solomonic columns” used by Raphael to “make monumental … twisted pillars in bronze below the central dome of St. Peter’s,” prevalent architectural elements still viewable today (Delmarcel 144-145).

It is the architectural elements of the columns which are notable in the composition of the painting “The Family of Henry VIII.” Margaret Mitchell proposed in an article in 1971 that the Henrican tapestries were not a gift from Leo X but plausibly, “that Henry purchased the set for himself some time before 1528, taking this date as a terminus ante quem…. If this was the case, it would be remarkable evidence of the reception of Italianate aesthetics at the English court during this period” (Campbell “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII” 72).

Set-off by the styling of the decoration and architecture are the royal figures and the two individuals “at the two ends of the picture are Will Somers and Jane the Fool, standing in doorways…” (Law 238). These household members are “in transitory motion, walking in a real garden against the asymmetric forms and vernacular materials of real buildings. The Family of Henry VIII appears, in summary, to have been conceived as much as an architectural image, as it was a group portrait; and one, moreover, that anticipated an audience familiar with architectural imagery as both as a liberal means of representing buildings and as a vehicle for abstract cultural or political discourse” (Rawlinson 110-111).

Fools

Paintings from this time show the prominent position that ‘natural fools’ held in the royal family. Their intimate status within the royal circle does not make it surprising that two fools were included in the portrait of The Family of Henry VIII. “Their inclusion in this royal dynastic portrait suggests that fools had a distinct, privileged and vital role to play at the Tudor court” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools”). In this multiple portrait, “Will Somer and Jane the Fool appear on either side, flanking the family” (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15).

The status of a royal fool was ambiguous, somewhere between a family member, employee and serf. In the sixteenth century, a distinction was made between those who were “an ‘artificial fool’, a term that seems to have been synonymous with ‘jester’ was one who mimicked the ‘foolishness’ of the other” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools: Research”) and a natural fool a person “we recognise today as having a learning disability” (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15). The “popular myth about court fools and one that some historians have perpetuated is that they were simply clowns aping foolishness for a laugh” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools”). A “statute of 1540 establishes the royal prerogative over ‘idiots and fools natural’” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools). This lends to the belief that natural fools had some deficiency in judgment but were not out-right shunned nor ridiculed. In fact, ‘natural fools’ were “well cared for at the Tudor court and valued for their directness and humour, gaining a unique position in elite and royal society” (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15).

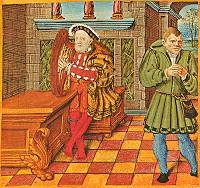

Henry VIII and his fool, Will Somers

Treatment of fools was not always positive throughout history but there is a turning point in Tudor England after the publication of Erasmus’ The Praise of Folly. Reminding humankind of its foolishness, Erasmus declared that “All mortals are unavoidably fools; and there is none wise but one, that is God” (Erasmus 172). Natural fools became viewed as “possessors of an essential goodness and simplicity that meant they were incapable of sin…. Their folly was wiser than wisdom (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools”). “Their perceived lack of guile, their directness and their humour were valued as assets” and they became integral to the court and occupied a unique and valued position (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15).

The acceptance and importance of fools at court manifests in the painting The Family of Henry VIII. Will and Jane “did not wear the harlequin’s motley and cap with bells familiar to us from images of court jesters at the time” (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15). Because they were attired in clothing of “high quality cloth and silk” one realizes they are considered natural fools and part of the household as favored retainers. Henry VIII relied on his fools to entertain him and relieve him from his melancholy. Comments a Courtier would never be allowed to say were often permitted by a fool. The qualities of fools, “their ability to bring mirth and their relationship to truth – explains their privileged, hallowed status that brought them both favour and authority at the court of Henry VIII” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools: Research”).

Jane or Mother Jak

Several people have been identified as the woman in the left doorway. Some historians believe it is Mother Jak, Prince Edward’s wet nurse. Who precisely was Mother Jak will never be certain. Despite Agnes Strickland’s claim it was Edward’s “first lisping accents” which altered Jackson to Jak (Strickland Lives of the Bachelor Kings of England 200), there is no proof of the surname or given name of the wet nurse known as Mother Jak. Further dispute leans towards whether Mother Jak is the person portrayed in the painting. Most likely she is not. The costume and obvious shorn head give stronger evidence that the portrayal is of Jane the Fool. ‘Jane the Fool’ was in the household of Princess Mary thus a “precedent was set for the inclusion of fools in royal family groups” (Weir “Two Newly Discovered Portraits of Elizabeth I as Princess”).

Jane, mentioned as early as 1537 in Princess Mary’s household, could have been orginally the fool that Anne Boleyn had purchased clothing for in the last months of her life. Even though Mary would not have been disposed to do a favor to Anne, Jane could have been appointed to her “care by the king or Cromwell” (Southworth). In April 1538 there is an “order for ‘a yerde & a halfe of Damske’ for a “gowne for Jane the Fole” with a pair of shoes ordered in 1542 and sheets in 1543 (Southworth).

Beyond clothing, money was spent on Jane’s medical care. Court records show “that there were eight payments of four pence a time for ‘shaving of Jane [the] fool’s head’ (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15). These entries suggest she developed a skin ailment which required her head to be shaved for many months. During this time it appears as if Queen Catherine Parr took a keen interest in Jane and perhaps, feeling as if Jane needed further occupation, in October 1544 she put in an order for “3 geese for Jane Foole 16d…and a hen for Jane Foole 6d” (Southworth).

This would be the time period of the royal family portrait. In it Jane wears “a tight-fitting cap to cover her recently shorn head and a brocaded damsk bodice and gown, parted at the front to show a pelated underskirt. To judge by her lively expression and arrested posture, the change of air and regime had had good effects” (Southworth). It is clear that Jane was “a familiar figure in the royal households, sufficiently known to be included in a peripheral role in the portrait as female equivalent and partner to the king’s innocent male fool, Will Somers” (Southworth).

After the portrait and one more mention in the rolls in 1546, Jane does not appear in many records until the reign of Queen Mary. Documents of the Exchequer show the request for clothing for Jane in the first year of Mary’s reign, 1553/1554. Silk, satin, damask, gold and other costly materials are shown in the documents which prove “Jane’s clothes as commensurate in quality with those to be worn by the queen’s ladies…and the number of gowns and accessories ordered for Jane is greater in number than those for any other person bar the queen herself” (Southworth). Interestingly, Jane was also included in the St. Valentine’s Day lottery. Each year lots were drawn by male courtiers to determine which lady would be their “partners for the evening’s dancing….” There are records in 1554 and 1558 of the gentlemen (Mr. Herte and Mr. Barnes repsectively) who were “Jane our Foole’s Valentyne” (Southworth). Throughout Mary’s reign, Jane was “elevated in status to an altogether grander, more prominent function in the recreations of the court” she was no longer left to fend for her geese and hens (Southworth). Whatever the quality of life, one cannot deny the generosity of Queen Mary.

In 1555 Jane suffered an ailment of her eyes and Mary paid for treatment and a nurse “for keping the said Jane during the time of the healing of her eye” (Southworth). The Queen’s watch over Jane did not extend to after her death. There are no records to verify Jane’s whereabouts. It is hoped that a lady-in-waiting or other household member took Jane under her wing.

Will Somer

The male retainer in the painting, The Family of Henry VIII, has been identified as Will Somer, or Somers and sometimes Sommers. Described as “lean and ‘hollow-eyed,’ and with a stoop,”the Shropshire born Will caught the attention of a wool merchant, “Richard Fermour …who brought him to Greenwich to be presented to the King” sometime after 1525 (Weir Henry VIII: The King and His Court 246).

Sources disagree on the level of Will’s disability, yet evidence suggests that Somer was a ‘natural fool.’ In 1600 “Robert Armin described Somer as ‘the king’s natural jester’” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools”). Somer needed a ‘keeper’, someone to look after and care for him, because people knew he could not care for himself. A warrant from 1551 approved “payment of 40 shillings to William Seyton ‘whom his Majesty hath appointed to keep William Somer’” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools”). It appears that although Somer needed someone to take care of him, he was “well paid, well fed and well clothed in return for his work in Henry’s court” (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15).

Robert Armin’s description of Will was footnoted in John Heywood. It is as follows:

“Leane he was, hollow eyde, as all report,

And stoop he did, too; yet in all the court

Few men were more belov’d then was this foole

Whose merry prate kept with the king much rule.

When he was sad, the king and he would rime:

Thus Will exiled sadness many a time” (Heywood 29).

Will’s popularity with the king was corroborated by contemporary anecdotes and he used the power he possessed for the best purposes. Armin says:

‘Hee was a poor man’s friend

And helpt the widow often in the end,

The king would even grant what he would crave,

For well he knew will no exacting knave,

But whisht the king to doe good deeds great store,

Which caus’d the court to love him more and more’” (Heywood 29).

Somers, in all probability, “owes his reputation rather to the uniform kindness with which he used his influence over bluff Harry, than to his wit or folly” (Armin 64). Well known for his “kindness and humility in his character” (Ettin 410), Will’s reputation “stemmed not from his comedy but from his compassionate character” (Ettin 407).

His compassion was demonstrated when the family of his previous employer fell unto hard times, and it was said that Will “dropped some expressions, in the king’s last illness, which reached the conscience of the merciless prince, and to have caused the remains of his estate which had been dismembered, to be restored to him” (Armin 65).

“Somers was that rare creature at court, a man of integrity and discretion, who refused to become embroiled in factional politics and who never took advantage of his privileged position. He remained one of the King’s closest companions during Henry’s later years” (Weir Henry VIII: The King and His Court 246).

Could a man with the quality of only kindness have influenced Henry VIII? Was the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography correct when its authors claimed that Will’s reputation for cleverness and wit owed “more to posthumous myth than to fact” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools”)?

It appears as if Will’s specialties were physical antics and witticisms. A letter from Sir William Paget to Henry VIII in 1545 credits Somer with “a habit for wise and quotable sayings” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools: Research”). By focusing on “clever play with language and extemporaneous versifying, he can be considered at the very least the first notable comedian of the English Renaissance, a jokester for the humanist age” (Ettin 406).

Observers believed he could “never forgo a jest. All his works contain witticisms; he cannot long remain solemn” (Harington 43). Will’s style was bold “indeed, he mocked the powerful; but as a result, it was they who lost favor rather than he” (Ettin 407). One anecdote tells how Will tricked Cardinal Wolsey out of 10 pounds.* “The king laught at the jest, and so did the cardinall for a shew, but it grieved him …yet worse tricks than this Will Sommers served him after, for indeed hee could never abide him, and the forteiture of his head had liked to have beene payed, had hee not poysoned himself” (Armin 47).

Somer was entertaining and proved popular despite his boldness and a few critics. It was claimed that, besides Cardinal Wolsey Sir Thomas More, “held disdain for the less intellectual and sophisticated Sommers” (Ettin 407). John Heywood, a dramatist, wit, entertainer and Somer’s contemporary, wrote “mayster Somer, of sotts not the best” (Heywood 22). A footnote in Heywood explains that a sot was the equivalent to fool and is described as a natural fool, or idiot (Heywood 32). But others, such as J. P. Collier, describes Will Somers in his introduction to the reprint of Armin’s Nest of Ninnies, as “a jester of a different character to the others, inasmuch as he was an artificial fool—a witty person, affecting simplicity for the sake of affording amusement. Jesters of this class … had their origin in the license allowed to the tongues of ‘innocents,’ as they were sometimes, for the sake of distinction, called” (Armin 19-20).

Whether with natural intelligence or with natural innocence Somer did amuse; and, most importantly, he amused the King. Henry VIII enjoyed rhyming games and he and Somer amused each other “trading or capping one another’s verses” Ettin 407). Few contemporaries disagreed with “Somer’s ability to use his ‘merry prate’ and aptitude for spontaneous rhyme to enhance his master’s wellbeing” (Lipscomb “All the Kings Fools”). Indulging in these games “apparently amused the king when ill health or the problems of state or matrimony left him seemingly beyond solace” (Ettin 407). As quoted above, Robert Armin’s verse claimed “When he was sad, the king and he could rime, /Thus Will exiled sadness many a time.” Henry appreciated the man “with the wickedly inventive sense of humour” (Weir Henry VIII: The King and His Court 93). “Somer ys a sot! Foole for a kyng” (Heywood 21).

Unlike others in the royal household, Somer was free to voice uncomfortable truths to Henry because he was his fool, and the King enjoyed his banter. Thomas Cromwell appreciated Will’s political usefulness and “had applauded the way in which he had, on many occasions, jokingly drawn the King’s attention to the abuses within his household” (Weir Henry VIII: The King and His Court 415). “Few others in the Tudor court would have dared to say such things (“The King’s Fools-Disability in the Tudor Court” 15).

Favored at Court, Somers “never sought to capitalize on his friendship with the king, kept in the background when not performing, and preserved his privacy” (Weir Henry VIII: The King and His Court 246). Of course, his absenteeism could have resulted in the fact that his ‘keeper’ would remove him although no specific records indicate this. To all intents and purposes, Will seems to have earned the trust of the King and remained in royal service up until his retirement and death in the time of Queen Elizabeth.

With the purpose of the painting, The Family of Henry VIII, set to embody the power of the monarchy via the depiction of the King, his family and close household members amongst the affluence of his palace, success can be declared. Although by an unknown artist, the Italianate influence— perhaps a nod to the Papacy— is unmistakable as Henry flaunts his dynastic success: the Tudor dynasty is prosperous and secure.

*Geometria, is a “manuscript on the science of geometry” attributed to Thomas Berthelet and dedicated to Henry VIII possibly in the year 1541 (Davenport 19).

**£300 in 1640 would equate to £46,680 in 2014 values—based on the information from Measuring Worth website.

References

Armin, Robert. Fools and Jesters: With a Reprint of Robert Armin’s Nest of Ninnies 1608. London: Shakespeare Society, 1841. Google Books. Web. 25 Oct. 2014.

Bolland, Charlotte and Tarnya Cooper. The Real Tudors: Kings and Queens Rediscovered. London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2014. Print.

Breeze, Camille Myers. “The History of Tapestry Conservation and Exhibition at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.” International Tapestry Journal 2.4 (Winter 1996). Web. 5 Aug. 2014.

Campbell, Thomas. “School of Raphael Tapestries in the Collection of Henry VIII.” The Burlington Magazine 138.1115 (1996): 69-78. JSTOR. Web. 8 Sept. 2014.

Campbell, Thomas Patrick and Elizabeth A. H. Cleland. Tapestry in the Baroque: New Aspects of Production and Patronage. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010. Google Books. Web. 2 Aug. 2014.

Campbell, Thomas. Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. Google Books. Web. 7 Sept. 2014.

Campbell, Vera. “The Loukmanoff Cartoons.” Art Journal. 65. (1903): 103-108. Google Books. Web. 30 Aug. 2014.

Cheney, Iris. John Shearman: Raphael’s Cartoons in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen and the Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel. 56. 4 (1974): 607-609. JSTOR. Web. 18 Oct. 2014.

Davenport, Cyril F.S.A. Royal English Book Bindings. London: Seeley and Co. Limited. 1896. Google Books. Web. 14 Aug. 2014.

Delmarcel, Guy. Flemish Tapestry. Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo Publishers, 1999. Google Books. Web. 7 Sept. 2014.

Digby, George Wingfield. “English Tapestries at Birmingham.” The Burlington Magazine 93.582 (Sept. 1951): 294-296. JSTOR. Web. 8 Sept. 2014.

Dolman, Brett. “Wishful Thinking: Reading the Portraits of Henry VIII’s Queens.” Henry VIII and the Court: Art, Politics and Performance. Ed. Thomas Betteridge and Suzannah Lipscomb. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2013. Google Books. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Doran, Susan. The Tudor Chronicles 1485-1603. New York: Metro Books, 2008. Print.

Erasmus, Desiderius. Erasmus in Praise of Folly, Illustrated with Many Curious Cuts, Designed, Drawn, and Etched by Hans Holbein and His Epistle Addressed to Sir Thomas More. London: Reeves & Turner, 1876. Google Books. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.

Ettin, Andrew Vogel. “Will Sommers.” Fools and Jesters in Literature, Art, and History: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. Ed. Vicki K. Janik. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1998. Google Books. Web. 25 Oct. 2014.

The Family of Henry VIII. Royal Collection Trust, 2014. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Harington, John. The Letters and Epigrams of Sir John Harington Together with the Tryse of Private Life. Ed. Norman Egbert McClure. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1930. Internet Archive. Web. 25 Oct. 2014.

“Henry’s Court: The Fools.” Under These Restless Skies. n.d. Blog Web. 4 Aug. 2014.

Heywood, John. A Dialogue on Wit and Folly. London: Percy Society, 1845. Google Books. Web. 25 Oct. 2014.

Hunter, George Leland. “The Story and Texture Interest of Tapestries.” The Century: A Popular Quarterly, Volume 89. Ed. Josiah Gilbert Holland and Richard Valson Gilder. 601-612. New York: New Century Company, 1915. Google Books. Web. 5 Aug. 2014.

Hunter, George Leland. Tapestries, Their Origin, History and Renaissance. “Mortlake, Merton, and Other English Looms Chapter V.” 105-152. New York: John Lane Company, 1912. Google Books. Web. 4 Aug. 2014.

Jones, Mark. “Raphael’s Cartoons and Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel Announced at the V&A.” artdaily. artdaily/news.com, 28 May 2010. Web. 2 Aug. 2014.

Killikelly, Sarah H. Curious Questions in History, Literature, Art and Social Life: Designed as a Manual of General Information. Vol II. Pittsburgh: Joseph Eichbaum & Co., 1889. Google Books. Web. 2 Aug. 2104.

“The King’s Fools – Disability in the Tudor Court.” Disability in Time and Place. Ed. Simon Jerrett. English Heritage Disability History, 2012. n. d. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Klos, Naomi Yavneh, Ph.D. “Mini-Majesty: Dynasty and Succession in the Portraiture of Henry VIII and Edward VI.” King Henry VIII. 27 Oct. 2013. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Law, Ernest Philip Alphonse. The History of Hampton Court Palace Vol. I: Tudor Times. London: George Bell and Sons, 1890. Google Books. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

“Liechtenstein: The Princely Collections.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985. Google Books. Web. 19 Oct. 2014.

Lipscomb, Suzannah. “All the Kings Fools.” History Today. HistoryToday.com. 61. 8 (2011). Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Lipscomb, Suzannah, Elizabeth Hurren, and Thomas Betteridge. “All the Kings Fools: Research.” All the Kings Fools. Ed. Peet Cooper. Foolscap Productions, 2011. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Lloyd, Christopher and Simon Thurley. Henry VIII: Images of a Tudor King. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1990. Print.

Morris, Sarah and Natalie Grueninger. In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. 2013 Google Books. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Muntz, Eugene. Raphael: His Life, Works and Times. London: Chapman and Hall, 1888. Google Books. Web. 6 Aug. 2014.

Passavant, Johann. Raphael of Urbino and His Father Giovanni Santi. London: MacMillan and Co., 1872. Internet Archive. Web. 6 Aug. 2014.

Peck, Linda Levy. Consuming Splendor: Society and Culture in Seventeenth-Century England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Google Books. Web. 18 Oct. 2014.

“The Raphael Cartoons.” Victoria and Albert Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. 2014. Web. 2 Aug. 2014.

Rawlinson, Kent. “Architectural Culture and Royal Image at the Henrician Court.” Henry VIII and the Court: Art, Politics and Performance. Ed. Thomas Betteridge and Suzannah Lipscomb. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2013. Google Books. Web. 1 Aug. 2014.

Scharf, George. A Descriptive and Historical Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures at Woburn Abbey: First Part, Portraits. London: Bradbury, Agnew & Co., 1877. Google Books. Web. 2 Aug. 2104.

Shafe, Laurence. Art and Architecture at the Tudor Court. 2010. Web. 8 Aug. 2014.

“Sir Franics Crane English Tapestries.” Grafton Regis. Village of Grafton Regis, n. d. Web. 20 Sept. 2014.

Southworth, John. Fools and Jesters in the English Court. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2011. Google Books. Web. 24 Oct. 2014.

Strickland, Agnes and Elisabeth Strickland. Lives of the Bachelor Kings of England. London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1861. Google Books. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.

Strong, Roy. Gloriana. London: Pimlico, 2003. Print.

Thomson, William George. A History of Tapestry from the Earliest Times Until the Present Day. New York: G. P. Putnam’s and Sons, 1906. Google Books. Web. 18 Oct. 2014.

Thurley, Simon. The Royal Palaces of Tudor England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. Print.

Weir, Alison. Henry VIII: The King and His Court. New York: Ballantine Books, 2001. Print.

Weir, Alison. “Two Newly Discovered Portraits of Elizabeth I as Princess.” Alison Weir. Alison Weir, n.d. Web. 14 Aug. 2014.

Agnes Strickland,Alison Weir, Andrew Ettin, Anthony Denny,Arras, Banqueting House, Basilica of St. Peter, Berlin Museum,Bernini, Brett Doleman,Brussels, Camille Myers Breeze, Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga,Cardinal Wolsey,Catherine Parr, Charles I, Charlotte Bolland,Christopher Lloyd,Cyril Davenport,Desiderius Erasmus,Dom Luis Mendez de Haro, Don Alonso de Cardenas, Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga of Mantua, Elizabeth Cleland, Elizabeth I,Elizabeth Regina,Elizabethan,Elizabethan England,English History,Erasmus, Ernest Law,Eugene Muntz, Feast of St. Stephen,Flanders, Francis Clein,Francis Cleyne, Garde-Meuble National,Genoa, Geometria,George Digby, George Hunter, George Scharf,Giorgio Vasari, Great Garden of Whitehall,Greenwich, Guy Delmarcel, Gwillim Stretes, Hampton Court, Hans Holbein,Healing of the Lame Man, Henry VIII, Hohn Heywood, Iris Cheney,Jane Seymour, Jane the Fool, Johan Wolfgang Goethe, Johann Passavant, John Harington, John Southworth, Katherine Parr, Kensington Cartoons, Kent Rawlinson, Lady Elizabeth, Lady Mary,Laurence Shafe, Linda Levy Peck, Lord Portector, M. Charles Blane, Margaret Mitchell, Mark Jones,Marques del Carpio,Michelangelo,Mortlake, Mother Jak,Naomi Yavneh Klos,Natalie Grueninger,Nest of Ninnies, Oliver Cromwell, Peter Aelst,Peter Paul Rubens,Peter van Aelst, Pope Leo X, Praise of Folly,Prince Edward, Quatre de Quincy, Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary,Raphael, Raphael Cartoons, Raphael d’Urbino, Robert Armin, Roy Strong,Sarah killikelly, Sarah Morris, Simon Thurley,Sir Christoopher Wren,Sir Francis Crane, Sir Thomas More, Sir William Paget, Sistine Chapel, South Kensington Museum,St. Paul, St. Peter,Susan Doran,Suzannah Lipscomb,tapestry, Tarnya Cooper, Thomas Campbell, Thomas Cromwell, Tomaso Vincidor di Bologna,Tower of London,Tudor, Tudor Court,Tudor Dynasty, Tudor History, Vatican, Vera Campbell, Victoria and Albert Museum,Whitehall Palace, Will Somer, Will Sommers,William III, William Thomson

Queen Mary is SO beautiful! 😍😍😍😍😍 the star of the portrait

Here’s a thought, the A pendant is not an A but a Greek Pi for Parr