On Friday, August 22, 2003, it was arranged for this blogger to meet the PR Manager of HM Tower of London (am withholding the name due to privacy) for access to the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula from 9:00 until 9:45. My excitement grew as, at the Pass Office, the PR Manager welcomed me. While she gathered the keys to the church she explained that the restricted entry was a policy resulting in the sacredness of the site. Since my visit, the availability to view the church has increased—tourists can now enter during the final hour before closing.

Exterior of the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London.

Described by John Noorthouck in his book, A New History of London published in 1773, St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower “was founded by Edward III and dedicated to St. Peter in chains. This is a plain Gothic building void of all ornament: 66 feet in length, 54 in breadth, and 24 feet high from the floor to the roof. The walls, which have Gothic windows, are strengthened at the corners…. The tower is plain, and is crowned with a turret” (Noorthhouck 768). This rather clinical description did not reveal the picturesque chapel this blogger encountered.

As we walked through the Tower precincts, the PR Manager made clear that the Chapel is first and foremost a parish church and the residents of the Tower have used it as such for centuries. As if to underline this fact, the parson’s cat roamed around while we were there.

By the 19th century with the Tower no longer a residence of the sovereign, the chapel became “regarded too much in the light of a mere ordinary parish church” (Bell 15). The hominess of the church is evident into the 21st century. Plain wooden pews top slab flooring. An exposed stonewall shelters the altar under which are the plaques (laid during the renovation completed in 1877) of those buried in the Chapel. Most of the bodies were placed in the crypt.

Doyne Courtenay Bell wrote, in 1877, of the Victorian Era restoration of the St. Peter ad Vincula. Bell had been granted access to the facilities and records by the Resident Governor of the Tower, Colonel Milman. Bell acknowledged that the records kept by Lord De Ros when he was Deputy Lieutenant of the Tower and his zeal in the restoration made it much easier for him (Bell) to write his book.

In 1862, entrances were altered so that the “insignificant porch on the south side, by which the building had been entered since the time of Queen Elizabeth, was removed, and the original old doorway at the west end, which had been bricked up and concealed by plaster” was reopened (Bell 10).

From this blogger’s point of view the most noteworthy alteration to the physical building was that the “lath and plaster covering was at the same time removed from the ceiling, and the old chesnut beams of Henry VIII’s roof were disclosed to view” (Bell 10). The ceiling was architecturally interesting and to know it was from the Tudor Era specifically added to its importance.

The ‘chesnut’ beams.

Bell supported the information this blogger received during the time of her 2003 visit that after the initial changes done in 1862 further restoration was needed by 1876 because the flooring had become too uneven and dangerous. In that year Constable of the Tower of London, Sir Charles Yorke, submitted a plan to have the Chapel “architecturally restored to its original condition, and also suitably arranged as a place of worship for the use of the residents and garrison of the Tower” (Bell 10).

As the restoration began, Bell reported, the “necessity for relaying the pavement, which had sunk and become uneven in many parts, became very evident; it was at once seen that nothing could be done until a level and safe foundation was prepared, upon which the new pavement could be placed…” (Bell 15). Once the paving stones had been removed it was found “that the resting places of those who had been buried within the walls of the chapel during the troublous times of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, had been repeatedly and it was feared almost universally desecrated” (Bell 15). People familiar with the history of St. Peter ad Vincula know that in “this church lie the ashes of many noble and royal personages, executed either in the Tower, or on the hill, and deposited here in obscurity” (Noorthouck 768).

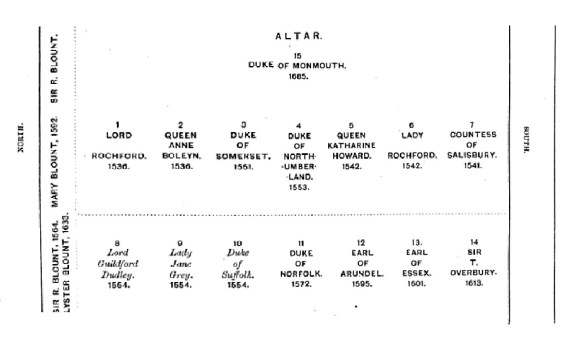

A list of some prominent personages buried near the altar.

It is beyond the scope of this blog to discuss all of the notable people inscribed on their memorial tablets in the chancel. There was still questionable evidence as to who was buried in the chancel at the altar and the placement of each person. At the time of the Duke of Monmouth’s burial, in 1685, a diagram of the suggested burial places of notable persons interred was created based on information compiled from several sources.

John Stowe first reported the use of a contemporary anonymous diary that John Gough Nichols later compiled with other sources in his Chronicle. Stowe described what happened after the executions of the Duke of Northumberland and two associates, “Theyr corpes, with the hedes, wer buryed in the chapell in the Tower ; the duke at the highe alter, and the other too at the nether ende of the churche” (Nichols 24). This placement was confirmed by Baker in his work. He stated that after the execution of the Duke of Northumberland “his body with the head was buried in the Tower, by the body of Edward late Duke of Somerset, (mortal enemies while they lived, but now lying together as good friends) so as there lieth before the high Altar in St. Peters Church, two Dukes between two Queens, namely, the Duke of Somerset, and the Duke of Northumberland, between Queen Anne, and, Queen Katharine, all four beheaded” (Baker 315).

The Duke of Somerset, Edward Seymour

Queen Anne Boleyn

The Duke of Northumberland, John Dudley

Queen Katherine Howard

Restorations are recorded to have occurred between the winter of 1876 and the spring of 1877 with the renovated chapel opened for service in June of 1877. At an initial meeting held to discuss the method of refurbishment attended by many worthies of the Tower administration, including Colonel Milman, it was decided to leave the more notable interments of the two queens and three dukes undisturbed near the altar. Typical of many a remodel, the agreed upon plan could not be carried out. The flooring was too unstable and after an examination by the Surveyor of the Office of Works, it was “decided that the pavement must be removed, but that as little disturbance of the ground as possible should take place” (Bell 17).

Bell gives us a brief run-down on the changes that were made. He reports that the old plaster and whitewash were removed from the walls and columns; a “piscina and hagioscope on the east wall of the aisle were discovered.” A wooden structure “which served as a vestry, was pulled down” and a new one was built “outside the eastern end of the aisle” (Bell 17). Sadly, none of my photographs show any of these religious architectural elements.

A more encapsulating photo of the Chapel St. Peter ad Vincula.

Despite acknowledging that many of the remains had been disturbed in centuries passed, Bell firmly believed that the female bones discovered during the reconstruction of the floor were of Anne Boleyn. He wrote, “not much doubt existed in the minds of those present that these were the remains of Anne Boleyn, who is recorded to have been buried in front of the altar by the side of her brother George Rochford, and these being the first burials in the chancel, the graves were in all probability dug to the right or dexter side of the altar, the so-called place of honour” (Bell 21). A description of Anne’s removal from the site of her execution, written 2 June 1536 by a Londoner, relayed that Anne’s ladies “fearing to let their mistress be touched by unworthy hands, forced themselves to do so. Half dead themselves, they carried the body, wrapped in a white covering, to the place of burial within the Tower. Her brother was buried beside her” (Gardiner 1036).

Not the grave marker of George, Viscount of Rochford but his wife, Lady Jane, who is buried near Queen Katherine Howard.

During the restoration of the winter of 1876-1877, hundreds of bones and partial skeletons were discovered. This ‘mere ordinary parish church’ witnessed many interments be they of notable, historical figures or parishioners. During my visit the PR Manager described the church as similar to a catacomb. The side chapel, actually a crypt, held many burial sites including the tomb of Sir Thomas More. With very few written, official documents precise locations of burials is impossible. It is similar to the locations of where people were kept in the Tower. Mostly the information comes from personal letters and historians piecing together where people must have stayed based on who they talk about, what they say they saw, or if lucky their mentioning that they were in such and such a tower. There is even some dispute as to where Elizabeth was housed when a prisoner–was she in the Bell Tower or in the royal apartments.

Bell Tower, part of the Tower of London

There was no inquiry on my part if there was any evidence that Elizabeth would have visited St. Peter ad Vincula when she was held prisoner I the Tower during her half-sister Mary’s reign. This blogger has already concluded that Elizabeth was too politically savvy and perhaps too anxious not to anger or upset her sister to do such a thing. Even as Queen she would not have ventured to her mother’s gravesite. To do so would have re-circulated old scandals and upset those subjects of more conservative leanings. She spent very little time in the royal apartments in the Tower of London. Upon her entry into London after her accession in 1558, she had to take formal and symbolic possession of the Tower. She entered on 28 November and stayed at least six days. Elizabeth returned 12 January 1559 to spend two nights prior to her coronation. It appears as if having fulfilled the requisite stay in the Tower Elizabeth never felt obliged to return. She had understood the poignancy of the place when, upon her formal entry that late November day, she remarked “Some have fallen from being Princes in this land to be prisoners in this place; I am raised from being prisoner in this place to be Prince in this land” (Marshall).

References

Baker, Richard, George Sawbridge, Benjamin Tooke, Thomas Clarges, Edward Phillips, and Edward Phillips. A Chronicle of the Kings of England, from the Time of the Romans Government, Unto the Death of King James the First.: Containing All Passages of State and Church, with All Other Observations Proper for a Chronicle. Faithfully Collected out of Authors Ancient and Modern; and Digested into a Method. By Sir Richard Baker, Knight. Whereunto Is Added, the Reign of King Charles the First, and King Charles the Second. In Which Are Many Material Affairs of State, Never before Published; and Likewise the Most Remarkable Occurrences Relating to King Charles the Second’s Most Wonderful Restauration, by the Prudent Conduct of George Late Duke of Albemarle, Captain General of All His Majesties Armies. As They Were Extracted out of His Excellencies Own Papers, and the Journals and Memorials of Those Imploy’d in the Most Important and Secret Transactions of That Time. London: Printed for Ben. Tooke ; A. and J. Churchill, at the Black-Swan in Pater-Noster Row; and G. Sawbridge, at the Three Flower-de Luces in Little-Britain, 1696. Google Books. Web. 15 Sept. 2013.

Bell, Doyne Courtenay. Notices of the Historic Persons Buried in the Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula, in the Tower of London. With an Account of the Discovery of the Supposed Remains of Queen Anne Boleyn. London: J. Murray, 1877. Google Books. Web. 14 Sept. 2013.

Denny, Joanna. Anne Boleyn: An New Life of England’s Tragic Queen. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press, 2006. Google Books. Web. 1 Sept. 2013

Gardiner, James (editor). “Henry VIII: June 1536, 1-5.” Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 10: January-June 1536 (1887): 424-440. British History Online. Web. 22 September 2013.

Hall, Edward, Henry Ellis, and Richard Grafton. Hall’s Chronicle; Containing the History of England, during the Reign of Henry the Fourth, and the Succeeding Monarchs, to the End of the Reign of Henry the Eighth, in Which Are Particularly Described the Manners and Customs of Those Periods. London: Printed for J. Johnson and J. Rivington; T. Payne; WIlkie and Robinson; Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme; Cadell and Davies; and J. Mawman, 1809. Archive.org. Web. 2 Jan. 2013.

Hibbert, Christopher. The Virgin Queen: Elizabeth I, Genius of the Golden Age. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1991. Print.

Hume, Martin A. Sharp. Chronicle of King Henry the Eighth of England: Being a Contemporary Record of Some of the Principal Events of the Reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, Written in Spanish by an Unknown Hand ; Translated, with Notes and Introduction, by Martin A. Sharp Hume. London: George Belland Sons, 1889. Internet Archive. Web. 4 May 2013.

Ives, Eric. The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn: The Most Happy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004. Print.

Marshall, Henrietta Elizabeth. “Elizabeth-How the Imprisoned Princess Became a Queen,” An Island Story: A History of England for Boys and Girls. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, Publishers, 1920. Web. 22 Sept. 2013.

Nichols, John Gough. The Chronicle of Queen Jane, Two Years of Queen Mary, and Especially of the Rebellion of Sir Thomas Wyat. London: J. B Nichols and Son, 1822. Google Books. Web. 17 June 2013.

Noorthouck, John. “Book 5, Ch. 2: The suburbs of the City.” A New History of London: Including Westminster and Southwark (1773): 747-768. British History Online. Web. 15 September 2013.

“The Queen Elizabeth Virginal.” V&A Images Collection. Victoria and Albert Museum, n.d. Web. 03 July 2013.

Ridgway, Claire. The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Countdown. UK: MadeGlobal Publishing, 2012. Print.

Somerset, Anne. Elizabeth I. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. Print.

Stevenson, Joseph (editor). “Elizabeth: September 1559, 1-5.” Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Elizabeth, Volume 1: 1558-1559 (1863): 524-542. British History Online. Web. 01 September 2013.

Walker, Greg. “Rethinking The Fall Of Anne Boleyn.” Historical Journal 45.1 (2002): 1. MasterFILE Premier EBSCOhost. Web. 2 Sept. 2013.

Warnicke, Retha. The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. Print.

Weir, Alison. The Children of Henry VIII. New York: Ballantine Books, 1996. Print

Weir, Alison. Henry VIII: The King and His Court. New York: Ballatine Books, 2001. Google Books. Web. 30 June 2013.

Weir, Alison. The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Jonathan Cape, 2009. Print.