Words to the Wise

What is wisdom? If we followed Aristotle’s idea of the practicality of wisdom not only would a person choose the best means to the ends or goals they may have, but also the ‘correct’ ends. Now the discussion takes on another dimension involving ethical choices. And where do we insert experiences, knowledge, perceptions, logic? Regardless of the definition of wisdom, is it applied differently depending on the person and their role in life, such as a ruler? If a head of state is expected to make decisions wisely, how do we judge the wisdom of the decisions? Is it simply because we agree with her or his choices?

We have much evidence that Henry VII and Elizabeth Regina were wise given the profuse use of the word to describe them both. With Henry we are assured that this “King, to speak of him in terms equal to his deserving, was one of the best sort of wonders, a wonder for wise men” (Bacon and Lumby 211). Praise indeed.

Henry VII Elizabeth Regina

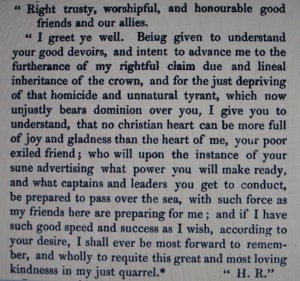

Both Polydore Vergil, an Italian priest who arrived in Britain in the year 1502 and was commissioned by King Henry VII to write a history of Britain, and Edward Hall, a Henrican contemporary, commented on Henry’s wisdom, shrewdness, prudence and resoluteness especially in moments of danger. “Kyng Henry being made wyse and expert with troubles and myschiefes before” in the time of his exile (Hall 435). Vergil and Hall also observed how the people respected his abilities and “no one dared to get the better of him through deceit or guile” (Vergil 144).

Polydore Vergil Edward Hall

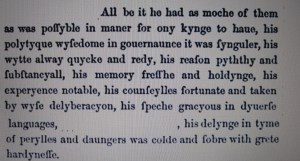

John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester spoke glowingly of Henry. Below are the text and the modern script of his oratory about Henry:

John Fisher

All be it he had as much of them

as was possible in manner for any king to have, his

politic wisdom in governance it was singular, his

wit always quick and ready, his reason pithy and

substantial, his memory fresh and holding, his

experience notable, his counsels fortunate and taken

by wise deliberation, his speech gracious in divers

languages … his dealing in time

of perils and dangers was cold and sober with great

hardiness.

Francis Bacon also reported that Henry’s “wit increased upon the occasion; and so much the more, if the occasion were sharpened by danger. Again, whether it were the shortness of his foresight, or the strength of his will, or the dazzling of his suspicions…” (Bacon and Lumby 219).

Henry’s suspicions made him guarded in his dealings with others, in his plans and his strategies. Perhaps it was this guarded behavior that led to the many chroniclers referring to him as shrewd. He was “undoubtedly shrewd, calculating, and long-headed; he seems never to have been overcome by passion” (Elton 16).

He was so shrewd he could make good use of what little advantages he had and in turn he was not a man of whom people could take advantage. Henry was very prudent in his selection of advisors. He “cogregated together the sage councelers of his realme, in which coiisail like a prince of just faith and true of promes… (Hall 423).

Men wanted to serve him but they could not tell what was on Henry’s mind. As a “wise Prince, it was but keeping of distance, which indeed he did towards all; not admitting any near or full approach, either to his power, or to his secrets: for he was governed by none” (Bacon and Lumby 215).

“Few indeed were the councillors that shared his confidence, but the wise men, competent to form an estimate of his statesmanship, had but one opinion of his consummate wisdom” (Gairdner 209).

Henry could not be called a learned man yet he was a lover of learning and gave his children an excellent education (Gairdner 217). Famously in 1498-99 Erasmus met with the then future Henry VIII when he was eight in 1498-1499 and still in the royal nursery at Eltham in Kent. Henry appreciated the humanist movement and ensured his sons were grounded in a classical education. Henry VII supported universities as well as his wife’s and mother’s patronage of colleges. He purchased books and acquired a library. “He was rather studious than learned; read most books that were of any worth, in the French tongue, yet he understood the Latin, as appeareth in that cardinal Adrian and Others, who could very well have written French, did use to write to him in Latin” (Bacon and Lumby 218). John Fisher spoke of Henry knowing many languages, the “fruit of his long exile” (Fisher). Perhaps the best ‘education’ he had was the exposure to various governmental methods while in exile and visiting other Courts in Brittany and France.

Exterior and Interior of Eltham Palace

Henry brought with him the experiences and knowledge of the cultures of France, Burgundy and Brittany with the secular classical themes. “This trend had already been apparent at Edward IV’s court, but Henry was an important influence in encouraging trends which were to lead to the flowering of Renaissance culture at the Tudor court in the 16th century” (Loades 71). He made “princely use of his wealth, encouraged scholarship and music as well as architecture, and dazzled the eyes of foreign ambassadors with the spendour of his receptions” (Gairdner 9).

Ambassadors were astonished not only with his Court but with the depth of knowledge he displayed of the situations in their own countries and “that they did write ever to their superiors in high terms, considering his wisdom and art of rule: nay, when they were returned, they did commonly maintain intelligence with him” (Bacon and Lumby 216)

Henry’s prudent policies, circumspect behaviors and political wisdom earned him high praise from contemporaries and historians. “He was of an high mind and loved his own will and his own way, as one that revered himself and would reign…” with triumph as he excelled at so many things (Bacon 793). He was successful. He was prudent. He was wise. He was emulated by his granddaughter, Elizabeth Regina.

Events in Elizabeth’s childhood taught her not to speak or act unwisely; her very life depended upon deliberate, cautious actions. These early lessons contributed to her wisdom and, along with her characteristics of intelligence, tenacity, compromise, and subtlety, she became well-respected. Even after centuries, most historians and chroniclers explain “even her errors of taste and judgment as superlative examples of political skill” (Elton 262).

Author Jasper Ridley is one of the few dissenters. He proposed that the truth was that “Elizabeth was an emotional woman, and often acted on impulse, and not from cunning political calculation” (Ridley 41). Her successes were not by good policy and planning, “but by luck, by muddling through…” (Ridley 335).

As much as one respects the interpretation of Ridley, overwhelming examples, even if disregarding sycophantic inclinations of contemporaries, show her intelligence and wisdom.

Maximilien de Bethune, Baron de Rosny, ambassador from France, exclaimed “this great Queen merited the whole of that great reputation she had throughout Europe” concerning her grasp for the political situation in Europe (Hibbert 115). Even as she aged, diplomats were still astounded at her grasp of affairs of state. Andre de Maisse, the French ambassador, thought her shrewd, calculating, statesmanlike and well-informed.

Baron de Rosny Andre de Maisse

Her Clerk of the Council, Robert Beale, believed that she was a “princess of great wisdom, learning and experience” and Sir John Harington wrote how Elizabeth would pass her judgment on matters and knew how to “cunningly commit the good issue to her own honour and understanding…” (Sitwell 87). Harington also observed that he “never did find greater show of understanding and learning than she was blessed with” (Hibbert 114).

Sir John Harington

The success of Elizabeth’s education is well-known and documented. Her preference for Roger Ascham as her tutor showed early on her judgment in men. He was an excellent choice and provided her not only a thorough education but a life-time love of learning. Even as queen, Elizabeth continued her studies as it was well-known she spent a part of her day reading and at study “by a wise distribution of her time” (Bohun 346). Ascham had nothing but praise for the quick mind and abilities of his pupil. Below, reproduced in its entirety is a letter Ascham wrote to his friend, Johannes Sturm, German scholar concerning Elizabeth:

“It is difficult to say, whether the gifts of nature or of fortune are most to be admired in my distinguished mistress. The praise which Aristotle gives, wholly centres in her; beauty, stature, prudence, and industry. She has just passed her sixteenth birthday and shows such dignity and gentleness as are wonderful at her age and in her rank. Her study of true religion and learning is most eager. Her mind has no womanly weakness, her perseverance is equal to that of a man, and her memory long keeps what it quickly picks up. She talks French and Italian as well as she does English, and has often talked to me readily and well in Latin, moderately in Greek. When she writes Greek and Latin, nothing is more beautiful than her handwriting” (Neale 14 – 15).

Princess Elizabeth and Sketch of Roger Ascham

Roger Ascham

Like her grandfather Henry VII, her skill in many languages allowed her to take a prominent role in the diplomacy of her country as she could meet with ambassadors herself. Her intellect allowed her to match the professional diplomats in subtlety and the language of diplomacy itself.

Elizabeth’s skills in government did not come from specific training as an apprentice but from her formal, classical and humanist education and her practical, political education of survival during her brother’s and sister’s reigns.

Without going into great detail, the young Elizabeth’s handling of the Thomas Seymour issue shows the intelligence, courage and composure she displayed while detained and questioned by Sir Robert Tyrwhitt. Tyrwhitt wrote the Lord Protector “I do assure your grace, she hath a very good wit, and nothing is gotten of her, but by great policy” (Erickson 88).

Another early example comes during her sister Mary’s reign. While under suspicion as part of the Wyatt Rebellion, Elizabeth negotiated with the councilors sent to arrest her to write a letter to Mary. Using her talents and education, Elizabeth not only composed a brilliant note, she also managed to utilize enough time that the tide had altered deflecting her move to the Tower for one more day. On the letter itself, she made diagonal marks at the end of the second page to ensure no one would tamper with the document.

Letter to Mary with diagonal lines across second page

As a mature and seasoned sovereign, Elizabeth continually dealt with complicated and life-threatening situations. Would all decisions be exact? Of course they would not. Yet, most historians agree with her contemporary John Hayward’s exclamation concerning her character that she was “in purpose, just; of spirit, above credit … as well for depth of judgment…” (Hayward 8). Maybe her wisdom came from knowing that her success came from serving England and her peoples and from making decisions that rested on the good of the kingdom. Or maybe it was simply she had a brain in her head and she used it:

“There is small disproportion betwixt a fool who

useth not wit because he hath it not and him

that useth it not when it should avail him”

Queen Elizabeth

References

Bacon, Francis. The Works of Lord Bacon: Philosophical Works. Longman and Co. 1858-1859. Google Books. Web. 11 Apr. 2013.

Bacon, Francis, and J. Rawson Lumby. Bacon’s History of the Reign of King Henry VII,. Cambridge: University, 1902. Internet Archive. Web. 22 Jan. 2013.

Bohun, Edmund. The Character of Queen Elizabeth, Or, A Full and Clear Account of Her Policies and the Methods of Her Government Both in Church and State, Her Virtues and Defects Together with the Characters of Her Principal Ministers of State … London: Printed for Ric. Chiswell at the Rose and Crown in St. Paul’s Church-Yard(IS), 1693. Google Books. Web. 26 Jan. 2013.

Commynes, Philippe de. The memoirs of Philip de Commines, Lord of Argenton: containing the histories of Louis XI and Charles VIII. Kings of France and of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. To which is added, The scandalous chronicle, or Secret history of Louis XI London: H. G. Bohn, 1855. Internet Archive. Web. 10 Feb. 2013.

Elton, G. R. England Under the Tudors. Third ed. London: Routledge, 1991. Print.

Fisher, John, and John E. B. Mayor. The English Works of John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester. London: N. Trübner for the Early English Text Society, 1876. Google Books. Web. 12 Feb. 2013.

Erickson, Carolly. The First Elizabeth. New York: Summit Books. 1983. Print.

Griffiths, Ralph A. and Roger S. Thomas. The Making of the Tudor Dynasty. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985. Print.

Hall, Edward, Henry Ellis, and Richard Grafton. Hall’s Chronicle; Containing the History of England, during the Reign of Henry the Fourth, and the Succeeding Monarchs, to the End of the Reign of Henry the Eighth, in Which Are Particularly Described the Manners and Customs of Those Periods. London: Printed for J. Johnson and J. Rivington; T. Payne; Wilkie and Robinson; Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme; Cadell and Davies; and J. Mawman, 1809. Archive.org. Web. 2 Jan. 2013.

Hayward, John, and John Bruce. Annals of the First Four Years of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth. London: Printed for the Camden Society by J.B. Nichols and Son, 1840. Google Books. Web. 19 Jan. 2013.

Hibbert, Christopher. The Virgin Queen: Elizabeth I, Genius of the Golden Age. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1991. Print.

Jones, Michael K. and Malcolm G. Underwood. The King’s Mother: Lady Margaret

Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Print.

Loades, David, ed. The Tudor Chronicles: The Kings. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990. Print.

Neale, J. E. Queen Elizabeth I. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1957. Print.

Norton, Elizabeth. Margaret Beaufort: Mother of the Tudor Dynasty. Stroud: Amberley, 2010. Print.

Okerlund, Arlene Naylor. Elizabeth of York. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. Print.

Penn, Thomas. Winter King; the Dawn of Tudor England. New York: Penguin Books, 2012. Print.

Pollard, Albert Frederick, ed. The Reign of Henry VII: From Contemporary Sources.[S.l.]: Longmans Green and, Co. 1913. Google Books. Web. 1 Apr. 2013.

Ridley, Jasper. Elizabeth I: The Shrewdness of Virtue. New York: Fromm International Publishing Corporation, 1989. Print.

Ross, Josephine. The Tudors, England’s Golden Age. London: Artus, 1994. Print.

Sitwell, Edith. The Queens and the Hive. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1966. Print.

Somerset, Anne. Elizabeth I. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. Print.

Vergil, Polydore, The Anglica Historia of Polydore Vergil, A.D. 1485-1537 (translated by Denys Hay), London: Office of the Royal Historical Society, Camden Series, 1950. Web. 29 Mar. 2013.

Weir, Alison. The Life of Elizabeth I. New York: Ballatine Books, 1998. Print.