Heir Unapparent

Looked at with a cursory glance, the roads to succession for the heirs to Henry VII and Elizabeth I was without challenge and smooth. Looked at with greater scrutiny, those roads to succession were troubled with opposition and rough. Although many other royal houses had issues, the House of Tudor developed unique situations.

The Oxford Dictionary lists the earliest use of the identification of the House of Tudor as the “Tudor Dynasty” to 1779 with it becoming much more prevalent around 1906. According to C. S. L. Davis, the name “Tudor” was not widely used in the sixteenth century. Davis continued to explain that the contemporary publications did not use the surname until 1584, speculating that the monarchs wanted to distance themselves as descendents from non-royal, actually lowly-born, origins.

Until the Yorkist view of legitimacy based on primogeniture, the law of succession was not clear. The dynastic struggles of the War of the Roses had continued the beliefs that the ruling king was such by divine right (having won the victory to place him there) and was cemented through the oaths of allegiance. Obviously, legitimacy was not in Henry VII’s favor but it is a doctrine which he embraced once he became king (Elton 18-19). Henry had the succession registered in Parliament. His purpose was to get his dynasty clearly declared. He had parliament issue forth “that the inheritance of the crown of England, with every right and possession belonging to it, should remain and abide with our now sovereign lord king Henry and his heirs” (Elton 19-20).

Upon his death, Henry VII’s throne did not move automatically to his son. Power brokers concealed his death for two days while they consolidated their positions. Henry VIII was proclaimed, but not given full sovereignty under the guise of his being shy of 18 years of age. Despite this, it cannot be denied that it was a smooth transition with no elaborate power plays. Henry VII may have thought this impossible at various stages of his reign.

Edward Hall claimed in the title of his history, “The Union of the two Noble and Illustrious Families,” that the children born to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York brought this about. There were claimants to the throne that had to be dealt with in various degrees of severity. The remaining daughters of Edward IV were married to supporters. John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, was a nephew of Edward IV and had been nominated as successor by Richard III. His oath of allegiance to Henry VII mitigated his claim. Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick, was handled less gently by being thrown in jail to dilute his dynastic claims. Henry realized “There had to be an end to dynastic war before any dynasty could set about rebuilding the kingdom” (Elton 10).

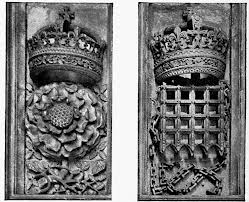

Heraldry of John de la Pole, Heraldry of Edward Plantagenet,

Earl of Lincoln Earl of Warwick

Also early in his reign Henry VII faced dangers to his less-than-stable throne in with not one but two pretenders as Duke of York. The first, Lambert Simnel, was quickly dealt with while the second, Perkin Warbeck, gained substantial support. William Stanley, brother to his own step-father, deserted the Tudor cause to support Warbeck as did the Dowager Duchess of Burgundy, Margaret of York. Her support proved so threatening that Henry was compelled to exclaim, “That stupid brazen woman hates my own family with such bitterness … she remains bent on destroying myself and my children” (Hutchinson 17).

Lambert Simnel Perkin Warbeck

Once the rebellions were stopped, Henry declared his second son Henry as Duke of York in order to claim the title and cement the succession of Lancaster and York. Preserving the Tudor succession continued to be in the forefront of Henry’s mind. Henry wanted to leave no inheritance pretenders to endanger his son’s position on the throne of England” (Ross 36). At the end of his reign he could know that the “threats of the dynasty had faded away; he could pass on a safe inheritance to his son” (Morrill 314). Although the throne was passed to the second son rather than the eldest (due to the early death of Prince Arthur) Henry VIII was the first sovereign in many years to inherit rather than win it by conquest. The crown that Henry VIII inherited was as strong as the one that James VI succeeded to from Elizabeth Regina.

Astoundingly it could be argued that the greatest issues of Elizabeth Regina’s reign, from Parliament’s perspective, were her marriage and the succession. Once Elizabeth passed the childbearing age, the question of her marriage took care of itself; and, obviously, affected the matter of the succession.

William Cecil tried to convince her that if she did not have children she would be in danger as people of “devilish means might be tempted to desire her end” as they tried to gain the throne and “she would have perpetual torment in life” (Froude 127).

Elizabeth’s perception was that settling the succession would not necessarily bring safety and stability. “I know that my people have no other cause for regret than that they know me to be but mortal, and therefore they have no certainty of a successor born of me to reign over them” (Sitwell 269). Debate would begin immediately, those slighted would be angry and it could still create a struggle for power upon her death. So, with her skill in statecraft, Elizabeth maintained her silence understanding the wisdom of this better than her advisors or her people.

Although in 1559 at her first Parliament Elizabeth assured the members that “the realm shall not remain destitute of an heir” she had no intention of clarifying who that person would be (Perry 100). She learned during her sister Mary’s reign that a monarch’s heir presumptive automatically becomes the center of dissent. “I have good experience of myself in my sister’s time, how desirous men were that I should be in place, and earnest to set me up. And if I would have consented, I know what enterprises would have been attempted to bring it to pass” (Marcus 66). Every person who had declared for her would have expected rewards when she became queen. They surely would have been disappointed in what had been meted out and would look around for someone else to put in place who would better reward them. “No prince’s revenues be so great that they are able to satisfy the insatiable cupidity of men” (Marcus 66).

Throughout her reign, various contenders took their turn leading the short list of possible heirs. Early on Katherine Grey held the prime spot. It was well-known that Elizabeth did not care for Katherine and when Katherine married in secret to Somerset’s heir, Elizabeth had no compunction about tossing her in the Tower. Katherine gave birth to two sons while confined who, despite their lineage, were never true contenders for the throne. Included in the list early in her reign would be Henry, Lord Hastings and Mary, Queen of Scots, who styled herself as Queen of England much to Elizabeth’s dismay, and never could be discredited as a true heir. Mary’s role will be discussed later.

Lady Katherine Grey Henry, Lord Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

As Elizabeth grew older the attention focused on the following claimants: Lady Arbella Stuart; Isabella, the Infanta of Spain; Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex; and, James VI of Scotland. She never could escape the political pressures to name an heir although she assured Sir William Maitland, Lord Lethington, a Scottish politician that “When I am dead, they shall succeed that have most right” (Neale 110).

Lady Arbella Stuart Isabella Clara Eugenia, Infanta of Spain

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

Small pox, that feared scourge of the 16th century became even more so when Elizabeth contracted it. She survived with minimal effects, but the fear instilled in her ministers of the possibility of her dying without an heir did not fade as quickly as her symptoms. During the 1563 Parliament petitions from both the House and the Lords were presented to her begging her to marry and to name an heir.

The House of Commons saw “the unspeakable miseries of civil wars, the perilous intermeddlings of foreign princes with seditious, ambitious and factious subjects at home, the waste of noble houses, the slaughter of people, subversion of towns … unsurety of all men’s possessions, lives and estates: if the sovereign were to die without a known heir, and pointed out that “from the Conquest to this present day the realm was never left as now it is without a certain heir, living and known” (Plowden Marriage with my Kingdom 130).

Elizabeth certainly gave a refined response on January 28, 1563. This short speech gave no concrete answer regarding the succession although she assured her listeners that she understood the gravity of the situation while letting them know that it was her concern for “I know that this matter toucheth me much nearer than it doth you all” (Marcus 71). She told them that it needed consideration, that she would let them know later and ‘so I assure you all that, though after my death you may have many stepdames, yet shall you never have a more natural mother than I mean to be unto you all” (Marcus 72).

The Lords sent an equally bloodcurdling petition about what would happen when Elizabeth died as they all knew that “upon the death of a prince, the law dieth” (Plowden Marriage with my Kingdom 131). Elizabeth’s response to the Lords was read out by Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper on April 10, 1563. As with the Commons she recognized that the succession was a grave matter and she would give it close attention. It was another brilliant example of an “answer, answerless” (Seaward).

Draft of Elizabeth Regina’s Speech Given to Parliament in April 1563

Elizabeth was not pleased when in 1566 members of Parliament brought up her marriage and the succession again. She told them they could not discuss it and they replied that they had a right to do so. Once more they received an adamant ‘no’ and a comment that “it is monstrous that the feet should direct the head” (Marcus 98).

Wrapped up very eloquently and fancily, Elizabeth replied to both the Commons and the Lords and, although the style of each response differed, the message was clear: when it was convenient for her to determine a successor she would and not before.

Elizabeth assured the members that she would marry when it was convenient and they were not to be concerned about that. She explained: “I will never break the word of a prince spoken in public place for my honor sake” (Marcus 95). As for the succession in no uncertain terms she reminded them that it was her decision and hers alone. Parliament had no business even discussing it and if the issue was debated it would be useless as “some would speak for their master, some for their mistress and every man for his friend…” (Marcus 97). One can imagine how incensed Elizabeth was as she had spoken that the Parliamentarians did not understand nor concern themselves with the peril she placed herself in by naming an heir. She believed “nothing was said for my safety, but only for themselves” (Marcus 96).

Next she derisively questioned if the named heirs would be able to go above their own personal interests for the good of the country. Would they “be of such uprightness and so divine as in them shall be divinity itself. …they would have such piety in them that they would not seek where they are the second to be the first, and where the third to be the second, and so forth” (Marcus 96). She made it clear that “at this present, it is not convenient, nor never shall be without some peril unto you and certain danger unto me” to name a successor so she would not (Marcus 97).

These admonishments did not silence the members and she had to threaten any Parliamentarian who brought up the issue of the succession with examination by the Privy Council and possible punishment which in turn led Paul Wentworth, on behalf of the House, to assert the right of freedom of speech.

This power struggle did not end there. Guzman de Silva, the Spanish ambassador whom she liked, learned about Parliament’s attempt to blackmail Elizabeth into naming a successor by placing in the preamble of the subsidy bill the necessity of the Queen to name her heir. Elizabeth caught this request while reading the draft of the subsidy bill and let it be known via annotations to the document, that she would not have her word questioned by being put into law form. “Shall my princely consent be turned to strengthen my words that be not themselves substantives? Say no more at this time; but if these fellows were well answered, and paid with lawful coin, there would be fewer counterfeits among them” (Mueller 40).

Guzman de Silva, Spanish Ambassador

In her speech to dissolve Parliament on January 2, 1567, she let the members have it again about the inappropriateness of bringing up the succession question as it was a concern only for her. She did not cloak her pique with Parliament. She had replied that “not one of them that ever was a second person, as I have been, and have tasted of the practices against my sister… I stood in danger of my life, my sister was incensed against me. …and I was sought in divers ways. And so shall never be my successor” (Marcus 96).

Draft of Elizabeth Regina’s Speech Given to Parliament on January 2, 1567

Mary, Queen of Scots plays a dominate role in the succession question under Elizabeth. At first it was as a thorn in the side of the English Queen because Mary, even when she was the Dauphine of France, styled herself “as heiress-presumptive to the English throne” (Fraser 118). Elizabeth was trying to establish herself as sovereign and Anglicanism as the Church and did not relish such threats to her country’s stability. Later, Mary conspired to overthrow Elizabeth and take over the crown of England—leading to her execution.

Mary, Queen of Scots as Dauphine of France

In between times, where does Mary fit? Many believed Mary was Elizabeth’s true choice as heir. It was reported by Sir William Maitland that Elizabeth compared the contenders to her throne alongside Mary. “You know them all, alas; what power or force has any of them, poor souls? It is true that some of them has made declaration to the world that they are more worthy of it than either she or I…” (Dunn 189). Yes, indeed. Elizabeth felt the succession question greatly, was concerned about the pool of contenders, and feared naming any one of them.

William Maitland, Lord Lethington

Maitland was certainly given every reason to believe that his Queen could obtain the throne of England as Elizabeth felt Mary had a legitimate right to it (even if she was angry at Mary for her self-declaration as heir and her use of Elizabeth’s arms in her heraldry) but she did couch her consideration in a warning. “For so long as I live there shall be no other queen in England but I, and failing thereof she cannot allege that ever I did anything which may hurt the right she may pretend” (Marcus 62).

Mary’s rights seemed to be overshadowed by all the reasons why she should not be heir: She was Catholic; Henry VIII’s will had excluded that branch of the family; and Scottish relations could deteriorate if the independent minded Scots felt threatened.

Yet, the greatest deterrent to actually naming Mary would be that as long as she thought she was in the running, she had to toe the line. Once declared, it would be harder for Elizabeth to control her. Elizabeth was convinced “it is hard to bind princes by any security where hope is offered of a kingdom” (Marcus 67). The risks of naming a successor were too great. Once Elizabeth gave the succession to someone, it was theirs. They had a right to keep it and it could not be taken back. One must see why the granting of it must be weighed so carefully.

The execution of Mary, Queen of Scots does not make this a moot point as the logical successor became Mary’s son, the Protestant James VI. For many years, Elizabeth maintained a correspondence with James which are available and well-worth checking out –one source, Letters of Queen Elizabeth and King James VI of Scotland: Some of Them Printed from Originals… edited by John Bruce. Historians have interpreted these letters to be in the line of a mentor and mentee. Obviously, her intentions were for him to succeed although she never would declare that because “to have done otherwise would have been to invite all rivals and enemies to set about forestalling his succession, thus jeopardizing both his rights and her domestic peace” (Neale 403).

Elizabeth astuteness understood the reality as she asserted “I know the inconsistency of the people of England, how they ever mislike the present government and has their eyes fixed upon that person that is next to succeed; and naturally men be so disposed: ‘Plures adorant solem orientem quam occidentem’ [More do adore the rising than the setting sun]” (Dunn 187 or Marcus 66).

References

Auchter, Dorothy. Dictionary of Literary and Dramatic Censorship in Tudor and Stuart England. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2001. Google Books. Web. 19 Mar. 2013.

Allen, William. Robert Parsons. A conference about the next succession to the crown of England: divided into two parts. The first containeth the discourse of a civil lawyer; how, and in what manner propinquity of bloud is to be preferred. The second containeth the speech of a temporal lawyer, about the particular titles of all such as do, or may pretend (within England or without) to the next succession. Whereunto is also added, a new and perfect arbor and genealogy of the descents of all the kings and princes of England, from the Conquest unto this day; whereby each mans pretence is made more plain. London: R. Doleman, 1594. Google Books. Web. 19 Mar. 2013.

Bacon, Francis, and J. Rawson Lumby. Bacon’s History of the Reign of King Henry VII,. Cambridge: University, 1902. Internet Archive. Web. 22 Jan. 2013.

Davis, C. S. L. “Tudor: What’s in a Name?” History Abstract 97.325 (2012): 24-44. Trove. Web.

Elizabeth I, James VI, and John Bruce. Letters of Queen Elizabeth and King James VI of Scotland: Some of Them Printed from Originals in the Possession of the Rev. Edward Ryder, and Others from a Manuscript. Which Formerly Belonged to Sir Peter Thompson, Kt. Vol. 46. [London]: Printed for the Camden Society, 1849. Google Books. Web. 22 Mar. 2013.

Elton, G. R. England Under the Tudors. Third ed. London: Routledge, 1991 Print

Fraser, Antonio. Mary Queen of Scots. New York: Delacorte Press, 1969. Print.

Froude, James Anthony. History of England from the Fall of Wolsey to the Defeat of the Spanish Armada. London: Longman, Green, 1908. Google Books. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Hall, Edward, Henry Ellis, and Richard Grafton. Hall’s Chronicle; Containing the History of England, during the Reign of Henry the Fourth, and the Succeeding Monarchs, to the End of the Reign of Henry the Eighth, in Which Are Particularly Described the Manners and Customs of Those Periods. London: Printed for J. Johnson and J. Rivington; T. Payne; Wilkie and Robinson; Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme; Cadell and Davies; and J. Mawman, 1809. Archive.org. Web. 2 Jan. 2013.

[Original Title–The union of the two noble and illustre famelies of Lancaster & Yorke…]

Hibbert, Christopher. The Virgin Queen: Elizabeth I, Genius of the Golden Age. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1991. Print.

Hutchinson, Robert. Young Henry: The Rise of Henry VIII. London: Weidenfeld &

Nicholson, 2011. Google Books. Web. 02 Dec. 2012.

Griffiths, Ralph A. and Roger S. Thomas. The Making of the Tudor Dynasty. New

York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985. Print.

Gristwood, Sarah. Arbella: England’s Lost Queen. London: Bantam Press, 2003. Print.

Jones, Michael K. and Malcolm G. Underwood. The King’s Mother: Lady Margaret

Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Print.

MacCaffrey, Wallace. Elizabeth I. London: E. Arnold. 1993. Print.

Marcus, Leah S. et al., eds. Elizabeth I: The Collected Works. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002. Print.

Morrill, John, ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of Tudor & Stuart Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. Print.

Mueller, Janel, ed. Elizabeth I: Autograph Compositions and Foreign Language Originals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003 Print.

Neale, J. E. Queen Elizabeth I. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1957. Print.

Norrington, Ruth. In the Shadow of the Throne: The Lady Arbella Stuart. London: Peter Owen Publishers, 2002. Print.

Norton, Elizabeth. Margaret Beaufort: Mother of the Tudor Dynasty. Stroud: Amberley, 2010. Print.

Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1991. Print

Penn, Thomas. Winter King; the Dawn of Tudor England. New York: Penguin Books, 2012. Print.

Perry, Maria. The Word of a Prince: A Life of Elizabeth from Contemporary Documents. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1990. Print.

Plowden, Allison. Marriage with My Kingdom: The Courtships of Elizabeth I. New York: Stein and Day, 1977. Print.

Plowden, Allison. Two Queens in One Isle: The Deadly Relationship Between Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 1999. Print

Ridley, Jasper. Elizabeth I: The Shrewdness of Virtue. New York: Fromm International Publishing Corporation, 1989. Print.

Roberts, Peter R. “History Today.” History Today Jan. 1986: n. page. History Today. History Today. Web. 12 Dec. 2012.

Seaward, Paul. “History of Parliament Online.” On This Day, 24 November 1586: Parliament’s Intervention against Mary, Queen of Scots. The History of Parliament Trust 1964-2013, n.d. Web. 23 Mar. 2013.

Sitwell, Edith. The Queens and the Hive. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1966. Print.

Somerset, Anne. Elizabeth I. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. Print.