Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd: Part III

Philip protected Elizabeth after the Wyatt and Dudley rebellions. She was indebted to him for her improved treatment by her sister, Queen Mary, and the Court. Philip “wisely determined that Elizabeth’s petty misdemeanours should be winked at” (Strickland 111). Why should activity, bordering on treason, be ignored? Elizabeth was the main heir with Mary, Queen of Scots and Dauphiness of France was second. Hapsburg interests had to prevent the balance of power in Europe from moving to the French. If Mary Stuart became Queen of England, France and Scotland, Spain would lose its hold on world affairs. Therefore, “this sudden kindness of Philip, who thought Elizabeth a much less obnoxious character than his father Charles the Fifth had conceived her to have been, did not arise from any regular principle of real generosity, but partly from an affection of popularity, and partly from a refined sentiment of policy” (Nichols 11).

Philip Understood Elizabeth Was the Best Heiress Presumptive

There were issues with Elizabeth as heir: first, her sister did not relish the thought of appointing a successor. Even when Philip sent his confessor “Fresneda to England to urge Mary to send a message to Elizabeth recognizing her as heir to the throne,” Mary refused (Ridley 72). The antagonism Mary felt toward Elizabeth was a difficulty that Philip knew he had to overcome. He did persuade Mary to make an effort at reconciliation and enfold Elizabeth into the Court. One-time Ambassador from Spain, Simon Renard, succinctly stated a second issue in June of 1555 he wrote a memorandum to Charles V outlining his concerns. “I foresee trouble on so great a scale that the pen can hardly set it down. Certain it is that the order of succession has been so badly decided that the Lady Elizabeth comes next, and that means heresy again, and the true religion overthrown. Churchmen will be wronged, Catholics persecuted; there will be more acts of vengeance than heretofore…. A calamitous tragedy will lie ahead” (Tyler XIII June 1555 216).

Spanish diplomats foresaw that if Elizabeth were to succeed, there would be religious revolution once again. But, what if she were married to a Catholic? Philip realized she was the only plausible successor to his wife and that Elizabeth would be queen because the people would not have it any other way. If he could use Elizabeth to promote Hapsburg interests and encourage her to be beholden to those interests, things would turn in his favor. Elizabeth could be a “demure, flatteringly deferential young lady” (Plowden 68). Philip saw no reason why with the right husband, suggested by her concerned and kindly brother-in-law, this ‘calamitous tragedy’ could be avoided.

The Savoy Marriage

What criteria would entail the right husband? He must be a Catholic, a Hapsburg ally or dependent with enough status to garner a marriage to a Queen Regnant.

In a memorandum prepared for Philip by Simon Renard, he let it be known that Elizabeth should marry the Duke of Savoy. This would have placed a lieutenant in England to help Queen Mary when Philip would be absent and help promote international relations (Plowden 65).

That early proposal between Elizabeth and Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, was suggested but came to nothing. Philip did not give up easily. According to several written sources upon meeting Elizabeth at Court, Philip “paid her such obeisance as to fall with one knee to the ground, notwithstanding his usual state and solemnity” (Nichols 11). He did not account for her resolve. “Elizabeth failed not to avail herself of every opportunity of paying her court to her royal brother-in-law, with whom she was on very friendly terms, although she would not comply with his earnest wish of her becoming the wife of his friend and ally, Philibert of Savoy” (Strickland 110).

Late in 1556, Philip again pursued this alliance. This time he put extreme pressure on Mary to ensure it took place. Letters between Mary and Philip show the tension this caused as he felt Mary should force Elizabeth to wed. She was reluctant to do that and used it as a way to get her husband back to England’s shores as then they could pray together to God—this was too weighty a matter to be determined without Him and him. Mary probably did not want Elizabeth to marry and produce an heir, strengthening her position for the throne; she also was reluctant to approve of it without the consent of Parliament. Philip implied if Parliament did not agree he would blame her. Mary wrote to him: “But since your highness writes in those letters, that if Parliament set itself against this thing, you will lay the blame upon me, I beseech you in all humility to put off the business till your return, and then you shall judge if I am blameworthy or no. For otherwise your highness will be angry against me, and that will be worse than death for me, for already I have begun to taste your anger all too often, to my great sorrow” (Porter 399).

Despite Mary’s protests of being held to blame, she did take steps to achieve Philip’s request. Elizabeth was sent for to join the Christmas Court. She arrived in London on 28 November and returned to Hatfield by 3 December. It was assumed the Queen brought up the subject of the marriage to Philibert and Elizabeth rejected the proposal. This topic has been more fully discussed in the blog entry, ‘Fate is Remarkable’, at https://elizregina.com/2013/03/12/fate-is-remarkable/

Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy

Elizabeth was allowed to return to Court before the end of February 1557. Philip returned to England in the spring of 1557 to gain support for his war with France and “to settle his scheme for the marriage of Elizabeth and Emmanuel Philibert” (Queen Elizabeth I 235). While he was successful in obtaining a commitment for the war, he was not successful regarding Elizabeth. Mary and Elizabeth both were stubbornly opposed to it. If Elizabeth were to marry Emmanuel Philibert, Philip would acquire a Catholic client state out of England. To him it would be a win-win situation. To Mary it was not. She could not sanction the alliance as it would be as good as handing Elizabeth the succession. Mary felt that Elizabeth should not be the Tudor heir because she was an illegitimate heretic. “Mary seems to have convinced herself that Elizabeth’s whole claim to royalty was fraudulent” (Loades Mary Tudor 169).

While the Queen had her reasons for not sanctioning her sister’s marriage, Elizabeth would not approve of the marriage either. She perceived that the succession had to clearly be acquired on her own, not as if it had been orchestrated by Philip

Marriage Proposal to the Crown Prince of Sweden

Elizabeth was acting with great circumspection so as not to jeopardize her position nor antagonize her sister. Therefore, when the King of Sweden, in the spring of 1558, sent an envoy to her to propose marriage between her and his son, she hastily informed him that any such request must first be submitted to the Queen and her Council.

King Gustav I Vasa of Sweden Eric, Crown Prince soon Eric XIV

Sir Thomas Pope informed Mary what had taken place. According to him, when Elizabeth let the Ambassador know in no uncertain terms that she would not treat with him, the Ambassador assured her that the king was “as a man of honor and a gentleman” who “thought it most proper to make the first application to herself” and that “having by this preparatory step obtained her consent, he would next mention the affair in form to her majesty” (Wart 96) . Evidently, Elizabeth informed the Swede that she “could not listen to any proposals of that nature, unless made by the queen’s advice or authority” and “that if left to her own will, we would always prefer a single condition of life” (Wart 97).

Mary was very pleased when she heard how Elizabeth had handled the situation. She called Sir Thomas Pope to Court to hear of the meeting first hand. She then commissioned Sir Thomas “to write to the princess and acquaint her with how much she was satisfied with this prudent and dutiful answer to the king of Sweden’s proposition.” He was then returned to Hatfield to stress to Elizabeth how much her conduct was appreciated by the Queen and also to find out what Elizabeth’s views were concerning matrimony in general. Pope was to “receive from her own mouth the result of her sentiments concerning it; and at the same time to take an opportunity of founding her affections concerning the duke of Savoy, without mentioning his name” (Wart 98). The Hapsburgs were still anxious to form another alliance between the English and Spanish crowns. Sir Thomas knew the importance of this to the Queen and did his best to carry out his mission and inform her of the results. On April 26, 1558, he informed the Queen of his conversation with Elizabeth when she responded to his questions concerning the Swedish and Savoy proposals and matrimony.

“Whereunto after a little pause taken, her grace answered in forme following, ‘Master Pope i requyre you, after my most humble commendaticions to the quenes majestie, to render unto the same lyke tahnkes, that it pleased her highnes of her goodnes, to conceive so well of my answer made to the same messenger; and herwithal, of her princelie consideration, with such speede to command you by your letters to signyfie the same unto me: who before remained wonderfullie perplexed, fering that her majestie might mistake the same: for which her goodnes I ackowledge myself bound to honour, serve, love, and obey her highnes, during my life. Requyring you also to saye unto her majestie, that in the king my brothers time, there was offered me a verie honorable marriage or two: and ambassadors sent to treat with me touching the same; whereupon I made my humble suit unto his highness, as some of honour yet living can be testimonies, that it would lyke the same to give me leave, with his graces favour, to remayne in that estate I was, which of all others best liked me or pleased me’” (Wart 99-100).

Elizabeth finished off her argument by stressing to Pope her sentiments. “And, in good faith, I pray you say unto her Highness, I am even at this present of the same mind, and so intend to continue, with Her Majesty’s favour: and assuring her Highness I so well like this estate, as I persuade myself there is not any kind of life comparable unto it” (Queen Elizabeth I 237).

Once the Princess’s response had been recorded, Pope informed Queen Mary what he then announced. “And when her Grace had thus ended, I was so bold as of myself to say unto her Grace, her pardon first required that I thought few or none would believe but that her Grace could be right well contented to marry; so that there were some honourable marriage offered her by the Queen’s Highness, or by Her Majesty’s assent. Whereunto her Grace answered, ‘What I shall do hereafter I know not; but I assure you, upon my truth and fidelity, and as God be merciful unto me, I am not at this time otherwise minded than I have declared unto you; no, though I were offered the greatest prince in all Europe.’ And yet perchance the Queen’s Majesty may conceive this rather to proceed of a maidenly shamefacedness, than upon any such certain determination” (Queen Elizabeth I 237-238). Here was a man who, as a product of his era and not understanding the true will of Elizabeth, could not fathom that she would not wish to marry.

Elizabeth in her Coronation Robes, less than a year after her interview with Pope

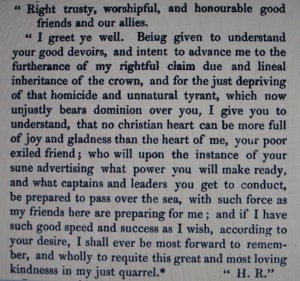

To complete the inquiry and perhaps to put her stamp on the response which Elizabeth must have known was being sent to her sister, she wrote a letter to Mary. The letter that follows comes to us from the historian Gregorio Leti’s sources.

“Madame, my dear Sister, However deeply I may

have fallen into disgrace with your Majesty, I have

always felt that you were so just and good that I

have never imputed the cause to anything but my

own ill-fortune. And even if my troubles had been a

thousand times greater they would have been incapable

of removing from my heart the loyalty and respect

which I owe to your Majesty. The ties of blood by

which we are united make me devotedly attached to

your interests, and I am ever inspired by a perfect

submission to the Royal and Sovereign authority of

your Majesty. The answer which I gave to the

Swedish ambassador is an evidence of my obedience;

I could not have replied in any other manner without

failing in my duty to you. But the thanks, which

you have been pleased to send me by Mr. Pope, is

only a part of your generous kindness, which has

filled me with affection and gratitude for you. I can

assure you, Madame, that since I have been old

enough to reason, I have had no other thought in my

heart for you except the love which one owes to a

sister, and, even more, the profound respect which

is due to a mistress and a queen. My feelings

will never change, and I should welcome, with

much pleasure, opportunities of showing you that I

am your Majesty’s very obedient servant and sister,

ELIZABETH” (Queen Elizabeth I 239).

Phantom Pregnancy of 1558—Its Foundation from 1556

“Philip was forced to acknowledge defeat” (Queen Elizabeth I 235). Elizabeth had evaded his attempts to influence her to wed. She remained in the background under the watchful eye of Sir Thomas Pope at Hatfield while the queen harbored hopes of another pregnancy. Philip’s brief visit to England in the spring of 1557 to untangle the Savoy and surprise Swedish marriage proposals and ask for military assistance was enough to raise the hopes of Mary that she was expecting a child. Responses by the principal parties, the Court and even the international diplomatic world to Mary’s declared pregnancy of 1557 were cemented in the events of 1556.

Back in 1556 Simon Renard kept Charles V informed of the minute details of Mary’s pregnancy telling the emperor “that one cannot doubt that she is with child. A certain sign of this is the state of the breasts, and that the child moves. Then there is the increase of the girth, the hardening of the breasts and the fact that they distill” (Tyler XIII June 1555 217).

Shortly thereafter Renard had to let the expectant grandfather know the reason he had not written to him with the good news. Apparently the Queen’s “doctors and ladies have proved to be out in their calculations by about two months, and it now appears that she will not be delivered before eight or ten days from now” (Tyler XIII June 1555 216).

Of one thing Renard was certain, “everything in this kingdom depends on the Queen’s safe deliverance.” He was incredulous “how the delay in the Queen’s deliverance encourages the heretics to slander and put about false rumours; some say that she is not with child at all…. Those whom we have trusted inspire me with the most misgivings as to their loyalty. Nothing appears to be certain, and I am more disturbed by what I see going on than ever before” (Tyler XIII June 1555 216). The Ambassador was concerned for Hapsburg and Catholic interests as members of the Privy Council were showing “an increasing amount of boldness and evil intentions” indicating a possible warming to the French (Tyler XIII June 1555 216).

These passages, except for the change of name and dates, could have been written in 1558. Philip had left England to lead his troop in the war against France but dutifully sent Count de Feria to Mary “to congratulate her on the announcement that she had sent him of her new hopes of an heir to the throne hopes which he probably knew to be illusory, though he so far humoured her as to say that her letter contained the best news that he had heard since the loss of Calais” (Queen Elizabeth I 239.

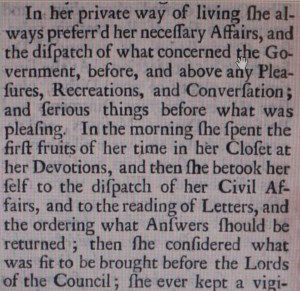

Upon their marriage Mary was 37 years old, eleven years older than Philip. She did not wear those years well. Years of stress, worry and ill-health had taken their toll on her. Now, several years into their marriage with one delusionary pregnancy behind her, chances were this would be too. Philip recognized her to be mortally ill since he had been out of the country for over a year and would have noticed the marked difference in her health that those close to home may have not detected. When he was back in Brussels he wrote to his sister and speculated what he “must do in England, in the event either of the Queen’s survival or of her death, for these are questions of the greatest importance, on which the welfare of my realms depend” (Tyler November 1558 502).

In the summer the Queen was clearly becoming weaker and weaker. “It was clear that there was no pregnancy” (Whitelock 327). By the end of October it “became apparent to everyone, Mary included, that she was not going to survive” (Porter 403).

Queen Mary died November 17, 1558. Foxe’s narrated from information he received from Rees Mansell, a gentleman of Mary’s privy chamber, that Queen Mary at “about three or four o’clock in the morning, yielded life to nature, and her kingdom to Queen Elizabeth her sister. As touching the manner of whose death, some say that she died of a tympany, some (by her much sighing before her death) supposed she died of thought and sorrow. Whereupon her council, seeing her sighing, and desirous to know the cause, to the end they might minister the more ready consolation unto her, feared, as they said, that she took that thought for the king’s Majesty her husband, which was gone from her. To whom she answering again, ‘Indeed,’ said she, ‘that may be one cause, but that is not the greatest wound that pierceth my oppressed mind:’ but what that was, she would not express to them. Albeit, afterward, she opened the matter more plainly to Master Rise and Mistress Clarencius (if it be true that they told me, which heard it of Master Rise himself); who then, being most familiar with her, and most bold about her, told her, that they feared she took thought for King Philip’s departing from her. ‘Not that only,’ said she, ‘but when I am dead and opened, you shall find Calais lying in my heart.’ And here an end of Queen Mary” (Foxe 330).

While Philip, the historic records shows, was courteous and gentlemanly toward her, affection did not seem to run too deep. In the midst of a business letter to his sister, Joanna of Austria, Princess Dowager of Portugal, Regent of Spain, Philip announced the death of his wife, Queen Mary concluding, “I felt a reasonable regret for her death” (Tyler November 1558 502). Maybe he was ‘made out of iron and stone.’

For references, please refer to the blog entry “Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd: Part I.”