Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd: Part II

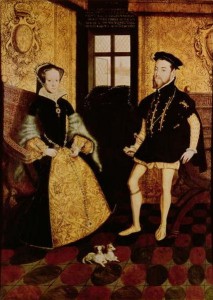

To understand the relationship between Elizabeth Regina and Philip II, a study must be made of the events of their association and the outcomes. These include two attempts to place Elizabeth on the throne during Mary’s reign; the role Philip played in how Elizabeth was treated in the aftermath of each rebellion; and Mary’s view of her sister’s place in the succession.

Wyatt Rebellion, 1554

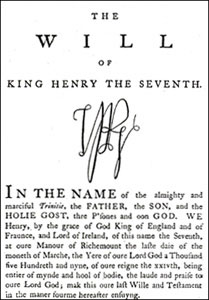

Sir Thomas Wyatt was the leader of a rebellion instigated in early 1554 by Mary’s proposed marriage to Philip of Spain. Once she became queen, Mary repealed the act which declared her parents’ marriage invalid and herself illegitimate. She was, as queen, a highly eligible match even though she was 37, certainly middle-aged in that era. She assured Charles V she would be guided by him in her selection of husband, and low and behold his son, Philip, a widower at 26, was the most eligible prince in Catholic Europe. Mary was determined to marry him.

The Wyatt Rebellion caused her to take decisive action. She went to the Guildhall and gave a speech to the populace assuring them that she married Philip only with the consent of her councilors and that she was firstly married to her kingdom.

Wyatt did enter London; Mary sent her troops after him. She did not flee and, while she was praying for her country’s safety, Wyatt was captured. The rebel said he took action being “persuaded, that by the marriage of the Prince of Spain, the second person of this realm, and next heir to the crown, should have been in danger; and I, being a free-born man, should, with my country, have been brought into bondage and servitude of aliens and strangers” (Strype 132). Rebellion was saving England from the Catholic scourge by ‘the second person of this realm.’ Thus, Elizabeth was implicated although Wyatt never named her during his interrogations or on the scaffold. Elizabeth was sent to the Tower for two months where she was held prisoner, questioned and intimidated.

Simon Renard, Ambassador to Spain, wrote to his sovereign, Charles V, 22 March 1554 that there was disagreement in the Council when “it was proposed to throw the Lady Elizabeth into the Tower, the Council expressed a wish to know exactly the reason, and the upshot was that the heretics combined against the Chancellor, and stuck to it that the law of England would not allow of such a measure because there was not sufficient evidence against her, that her rank must be considered and that she might perfectly well be confined elsewhere than in the Tower.” Renard relayed that no one would “accept the responsibility of taking custody of her.” Because of the councilors shying away from taking charge of Elizabeth, they “decided to conduct her to the Tower last Saturday, by river and not through the streets; but it did not happen that day, because when the tide was rising Elizabeth prayed to be allowed to speak to the Queen, saying the order could not have been given with her knowledge, but merely proceeded from the Chancellor’s hatred of her. If she could not speak to the Queen, she begged to be allowed to write to her. This was granted, and while she was writing the tide rose so high that it was no longer possible to pass under London bridge, and they had to wait till the morrow” (Tyler XII March).

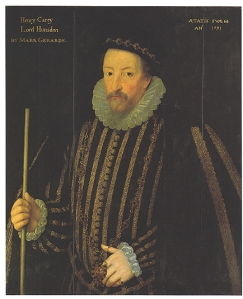

Simon Renard A Youthful Charles V

Elizabeth had achieved her purposes: she had postponed her imprisonment in the Tower and had written to her sister. This letter of March 16, 1554, one of Elizabeth’s most famous, was a marvel how she handled her sister and logically argued her innocence while writing under distressing circumstances.

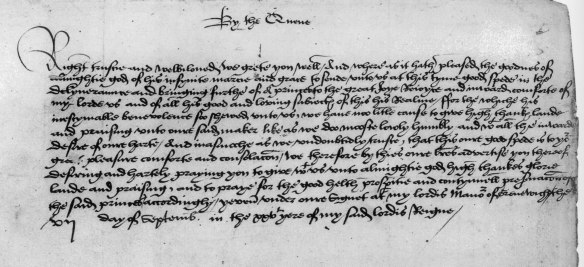

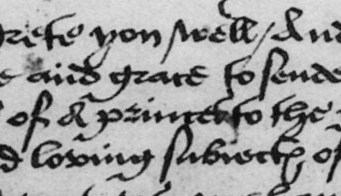

Elizabeth beseeched Mary to remember her agreement to Elizabeth’s request “That I be not condemned without answer and due proof.” Elizabeth wanted her sister to know that “I am by your Council from you commanded to go unto the Tower, a place more wonted for a false traitor than a true subject.” Although she bravely declared that she will go and be proved innocent, she pledged to her sister “I protest afore God that I never practiced, counseled, nor consented to anything that might be prejudicial to your person any way or dangerous to the state by any mean.” Elizabeth appealed for an opportunity to meet with the Queen to tell her in person of her innocence and asked her sister to pardon her boldness, excusing her actions “which innocency procures me to do, together with the hope of your natural kindness.…” The evidence of a letter written by Wyatt is addressed by logically stating “he might peradventure write me a letter, but on my faith I never received any from him.” Elizabeth completed the letter by making diagonal lines across the bottom so that nothing could be inserted and signed herself “Your highness’ most faithful subject that hath been from the beginning and will be to my end, Elizabeth” (Marcus 41-42).

The letter Elizabeth wrote to Mary in March of 1554

Her collaboration in the rebellion was never proven. Renard suggests that Gardiner “held documentary evidence of her [Elizabeth’s] active interest in the plot, but that he destroyed this because it also involved young Courtenay” (Queen Elizabeth 110). Not having direct proof of her sister’s guilt, Mary was reluctant to condemn Elizabeth and so released her to house arrest. John Foxe informed “The xix daye of Maye, the Ladye Elizabeth, Sister to the Queene, was brought oute of the Tower, and committed to the kepyng of Syr Henry Benifielde… shewed himself more harde and strayte unto her, then eyther cause was geven of her parte, or reason of his owne parte.” Foxe showed the surprise not in Bedingfield’s bad treatment but in the benevolence shown by Elizabeth once she came to the throne. Praising her for not taking revenge as other monarchs “oftentimes requited lesse offences with losse of life,” Foxe explained that Elizabeth did not deprive Bedingfield of his liberty “save only that he was restrained for not comming to the court” (Foxe V 1072).

When she was released from Woodstock, it was to come to Court to witness the birth of Mary’s heir. Sources differ on when Mary’s pregnancy was officially announced with some historians, such as Jasper Ridley, claiming it was in the spring of 1555 while we have an official document from January. The Doge Francesco Venier of Venice did send his Ambassador Giovanni Michiel instructions 5 January 1555 to congratulate the King and Queen on the “certainty now obtained of the Queen giving an heir to the realm” (Brown VI January 5). Further exclamations were extended for this “auspicious and desired event” concluding this was a “great gift conferred on the whole of Christendom” (Brown VI January 6).

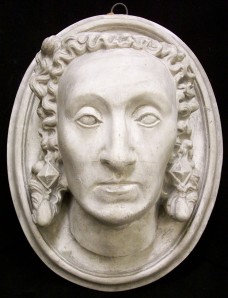

Francesco Venier, Doge of Venice

Regardless of when it was officially announced, the impending event did affect Elizabeth. On 29 April 1555, Michiel reported to the Doge, “that day or on the morrow Elizabeth Tudor was to arrive at Hampton Court from Woodstock.” Then on the 6th of May he informed the Venetian officials that when Elizabeth “appeared she was neither met nor received by anyone, but was placed in the apartment lately inhabited by the Duke of Alva, where she lives in retirement, not having been seen by any one, save once or twice by their Majesties, by private stairs” (Brown VIPreface 16).

Elizabeth was housed with a “certain Sir Thomas Pope, a rich and grave gentleman, of good name, both for conduct and religion; the Queen having appointed him Miladi’s governor. I am told …they also assigned her a widow gentlewoman, as governess, in lieu of her own who is a prisoner, she herself likewise may be also said to be in ward and custody, though in such decorous and honourable form as becoming” (Brown VI June 514). No ifs, ands or buts about it, Elizabeth was still under house arrest. Elizabeth’s release is credited to Philip’s influence on Mary. Philip realized without an heir born of Mary, Elizabeth would be the successor. To preserve Hapsburg interests, Philip realized Elizabeth had to be married to a Catholic prince: the intended bridegroom was Emmanuel Philibert, Prince of Piedmont and titular Duke of Savoy.

Philip had plans for Elizabeth. Antoine de Noailles wrote to the Queen-Dowager of Scotland in September 1555 informing her of Elizabeth’s popularity and the fact that “his Grace, the said Lord King, has shown a friendly disposition for her, and he has written several letters to the Queen, his wife, commending the Princess to her care” (Queen Elizabeth I 200).

Dudley Conspiracy, Late 1555 -1556

Another rebellion against the reign of Queen Mary began in December 1555. In a letter to Sir William Petre, Secretary of State, dated January 21, 1556, Nicholas Wotton, Dean of Canterbury and English Ambassador to France, wrote of information he had gleaned from an informant. There was a “plot against the Queen which he said was devised by some of the best in England, and so many were agreed thereupon that it was impossible but that it must take effect; that the matter had been in hand about a year ago.” The conspirators’ intentions were not to kill her Majesty “but to deprive her of her estate…” Wotton “did not think it necessary to write thereof to her Majesty lest she might suddenly be troubled with it, and conceive some greater fear of it than were good for her to do.” Petre was to inform the Queen when “it shall not disquiet her Majesty” (Turnbull 285-286). Mary was disquieted though and fearful for her life.

Sir William Petre Nicholas Wotton, Dean of Canterbury

Called the Dudley Conspiracy for the main instigator, Sir Henry Dudley (a distant relative to John Dudley, the executed Duke of Northumberland and Robert Dudley, the future favorite of Elizabeth), its purpose became clearer as the investigation continued. Mary and Philip were to be deposed and replaced by Elizabeth with her consort being Edward Courtenay.

Imprisoned during the time of Henry VIII, Courtenay spent 15 years in confinement. Released upon Mary’s ascension to the throne, he was created 1st Earl of Devon and sent on several diplomatic missions. His hopes of marriage to Mary fell flat when she espoused Philip. Courtenay then turned his attention to Elizabeth obviously seeing marriage as his way to the throne. After serving more time in the Tower for the Wyatt Rebellion, the Earl of Devon was exiled to Europe until his death in September of 1556. He found acceptance in Venice where he became the focal point for further conspiracies such as the Dudley Rebellion.

Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon

Several prominent supporters of the rebellion were Lord Thomas Howard, Sir Peter Killigrew, Henry Peckham and several members of the Throckmorton clan. One cannot underestimate the organization of Dudley and his fellow conspirators. They raised money, attempted to gain powerful allies such as the King of France and landed gentry, approached Courtenay and saturated England with anti-Catholic and anti-Spanish writings. It was subversive writings such as these that were found in the London residence of Kat Ashley, governess to Princess Elizabeth.

Giovanni Michiel, Ambassador to England for Venice kept the Doge and the Venetian Senate informed of what was occurring. Michiel reported on 2 June, “The number of persons imprisoned increases daily… Mistress [Katharine] Ashley was taken thither [to the Tower], she being the chief governess of Miladi Elizabeth, the arrest, together with that of three other domestics, having taken place in the country, 18 [Venetian] miles hence, even in the aforesaid Miladi’s own house [Hatfield], and where she at present resides, which has caused great general vexation. I am told that they have all already confessed to having known about the conspiracy; so not having revealed it, were there nothing else against them, they may probably not quit the Tower alive, this alone subjecting them to capital punishment. This governess was also found in possession of those writings and scandalous books against the religion and against the King and Queen which were scattered about some months ago, and published all over the kingdom” (Brown VIJune 505).

People close to Elizabeth knew about the plot — that has been well established. How involved was Elizabeth? The only written link between her and the rebels occurred in February 1556 when Anne, Duke de Montmorency, Constable of France wrote to the French Ambassador, Antoine de Noailles that “above all restrain Madame Elizabeth from stirring at all in the affair of which you have written to me, for that would be to ruin everything” (Queen Elizabeth I 203). Can this letter be seen as proof of Elizabeth’s willing cooperation with the Dudley plot? Although it is damaging, it is not conclusive. This could be a misinterpretation of information gathered by the Constable or wishful thinking.

Anne, Duke de Montmorency, Constable of France

Noailles and King Henri II were implicated in the Dudley plot. Because the international diplomatic scene had changed with the Vaucelles truce, Henri did not want to antagonize Charles and Philip so he “advised the conspirators to defer the execution of their plans” which they ignored (Acton 544). The success of the plot depended on too many people and too many variables (this blog will not relay the details there are many sources available including contemporary diplomatic dispatches in the Calendar of State Papers-Venice Volume VI). A conspirator, Thomas White, on staff at the Royal Exchequer was to ensure the robbery of funds to finance the conspiracy (Whitelock Mary Tudor 303). Ambassador Michiel wondered if White came forward “either from hope of reward, or to exculpate himself… revealed the plot to Cardinal Pole” (Brown VI March 5 434). White was rewarded as shown in the Originalia Roll (the fine roll sent to the Exchequer) for Mary and Philip because “of good and faithful service by our beloved servant, Thomas White, gentleman, in the late conspiracy against us, our crown and dignity attempted not long since by Henry Dudley and his accomplices” (Thoroton Society 52). A known conspirator rewarded: what of Elizabeth?

Convinced that Elizabeth was aware of the plot, Mary sent her trusted courtier, Francesco Piamontese, to Brussels to consult with Philip on how to handle the situation. Venetian Ambassador Michiel went further to explain that this issue was very sensitive because of Kat Ashley’s involvement “by reason of her grade with the “Signora,” who is held in universal esteem and consideration” (Brown VI June 505). So not only is a trusted servant of Elizabeth’s in possession of seditious materials, it appears to be universally acknowledged that Elizabeth is very popular. Would it be wise to move against her too aggressively? A tricky situation for Mary.

In June Michiel wrote to his superiors in Venice, “Finally, at the very hour when persons were departing, her chamberlain and the courier Francesco Piamontese returned” from Brussels to the Queen’s relief. “As for many months the Queen has passed from one sorrow to another” (Brown VI June 525).

So what was to become of Elizabeth? What guidance had Philip given his wife concerning the suspicions of her sister? What Mary received was pro-Hapsburgian advice. Despite Michiel’s predicitons, none of Elizabeth’s household members were executed nor was she punished. Although there was strong evidence that those around her were involved in treasonous activities (Kat Ashley being in posession of the seditious materials was enough cause for punishment beyond time in the Tower) and questions concerning what Elizabeth knew, any action against her would threaten her succession. “There is little doubt that it was the King’s influence which prevented Elizabeth herself from being again arrested on this occasion and sent to the Tower with the four other members of her household. It is difficult otherwise to account for Mary’s leniency” (Queen Elizabeth I 209).

Hapsburg interests demanded that Elizabeth be heir to the throne of England over Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary had the surest position of inheritance after Elizabeth and as the fiancé of the dauphin of France, could unite Scottish, French and English dominions and interests which would threaten the power of Spain. Hapsburg interests prevailed. “Piamontese returned to London with an unequivocal message from the king: no further inquiries should be made into Elizabeth’s guilt, nor any suggestion made that her servants had been implicated in the plot with her authority” (Whitlock 307). Philip was more than willing to be lenient with Elizabeth. By 1556 few people believed that Mary would produce an heir and looked toward Elizabeth to be the next queen. It probably was wise on the part of the councilors not to antagonize Elizabeth. She was considered the preferred heir, and her smooth succession could halt potential civil conflict or French interference to place Mary Stuart on the throne—both good enough reasons to leave well-enough alone.

So, astoundingly, Elizabeth remained free. Protestations of ignorance about her household’s activities were enough. Mary probably did not believe her but allowed the stories that Elizabeth’s name had been used without authority to be circulated. This blogger cannot help but feel for the position in which Mary was placed. Her motto, ‘Truth, Daughter of Time,’ seemed to be jeopardized as she did her husband’s bidding; although, with most of Mary’s submissiveness it was up to a point.

According to Michiel, in June of 1556 Mary sent two of her gentlemen, Sir Henry Hastings, and Sir H. Francis Englefield, to Elizabeth with a “message of good will…with a ring worth 400 ducats, and also to give her minute account of the cause of their arrest, to aquaint her with what they had hitherto deposed and confesssed, and to persaude her not to take amiss the removal from about her persons of similar folds, who subjected her to the danger of some evil suspicion; assuring her of the Queen’s good will and disposiiton, provided she continue to live becomingly, to Her Majesty’s liking. Using in short loving and gracious expressions, to show her that she is neither neglected nor hated, but loved and esteemed by Her Majesty. This message is considered most gracious by the whole kindom, everybody in general wishing her all ease and honour, and very greatly regretting any trouble she may incure; the proceeding having been not only necessary but profitable, to warn her of the licentious life led, especially in matters of religion, by her household” (Queen Elizabeth I 210).

Ambassador Michiel let on that Elizabeth’s household would be made up of persons the Queen believed to better serve her. It is assumed Mary thought her sister guilty and urged Elizabeth “to keep so much the more to her duty, and together with her attendants behave the more cautiously” (Queen Elizabeth I 210).

Mary feigned that she believed Elizabeth had been in danger of “being thus clandestinely exposed to the manifest risk of infamy and ruin.” So, the solution was for the Queen to remodel Elizabeth’s household “in another form, and with a different sort of persons to those now in her service, replacing them by such as are entirely dependent on her Majesty; so that as her own proceedings and those of all such persons as enter or quit her abode will be most narrowly scanned” (Brown VIJune 505).

Assigned to Elizabeth’s household was “Sir Thomas Pope, a rich and grave gentleman, of good name, both for conduct and religion; the Queen having appointed him Miladi’s governor, and she having accepted him willingly, although he himself did his utmost to decline such a charge. I am told that besides this person, they also assigned her a widow gentlewoman, as governess, in lieu of her own who is a prisoner, so that at present having none but the Queen’s dependents about her person, she herself likewise may be also said to be in ward and custody, though in such decorous and honourable form as becoming” (Brown VI June 514).

Pope was commissioned by Mary’s Council in July of 1556 to keep Elizabeth informed of the activities confessed by the Dudley conspirators “how little these men stick, by falsehood, and untruth, to compass their purpose; not letting, for that intent, to abuse the name of her Grace, or any others” (Queen Elizabeth I 213).

Elizabeth did write to the Queen in careful phraseology about the information she had received from Pope. “Of this I assure your majesty, though it be my part above the rest to bewail such things though my name had not been in them, yet it vexeth me too much …as to put me in any part of his [the devil] mischievous instigations. And like as I have been your faithful subject from the beginning of your reign, so shall no wicked persons cause me to change to the end of my life. And thus I commit your majesty to God’s tuition, whom I beseech long time to preserve … from Hatfield this present Sunday, the second day of August. Your majesty’s obedient subject and humble sister, Elizabeth” (Marcus 43-44).

For references, please refer to the blog entry “Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd: Part I.”