It is not the purpose here to debate whether or not a person can be completely prepared for death when it comes. Each person’s preparation must be unique and based on his or her views and life-choices. This preparation is most often done in private, but what if the person is a public figure—a sovereign? Now the natural process of death becomes a public experience. The deaths of both Henry VII and Elizabeth Regina were witnessed by a multiple people and recorded as part of the historic chronicle. Their foibles and quirks exposed and also their immense courage.

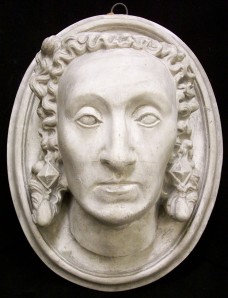

Death mask of Henry VII Replica death mask of Elizabeth I

Henry VII’s health was never robust and after he suffered the deaths of his son Arthur and his Queen, Elizabeth of York, in childbirth along with the baby he became more delicate and more frequently experienced bouts of ill-health. The Spanish ambassador, Pedro de Ayala, declared in a letter to Ferdinand and Isabella that “the king looks old for his years, but young for the sorrowful life he has led” (Bergenroth 178).

Pedro de Ayala, Spanish Ambassador

In early March of 1509 Henry became unwell at Hanworth, about six miles from Richmond to where he ordered the Court to move. By early April he was unable to eat and struggled for breath. Some historians believe he suffered from quinsy, complications to tonsillitis. Henry “lay amid mounds of pillows, cushions and bolsters” throughout the month of April (Penn 339).

Henry’s deathbed illness is not well-documented by narrative although we know several men who attended based on the scene depicted by Garter Herald Thomas Wroithesly. There are 14 figures placed around the bed with three doctors identified by occupation by the flasks in their hands including Giovanni Battista Boerio and two clerics, including Thomas Wosley. The other nine had their coats-of-arms painted above their heads; they were Bishop Richard Fox, Lord George Hastings, Richard Weston, Richard Clement, Sir Matthew Baker, John Sharp, William Tyler, Hugh Denys and William Fitzwilliam.

Henry VII on his death bed

Henry’s eyes being closed by Fitzwilliam

Henry lingered for some days until “having lived two and fifty years, and thereof reigned three and twenty years, and eight months, being in perfect memory, and in a most blessed mind, in a great calm of a consuming sickness passed to a better world, the two and twentieth of April 1509, at his palace of Richmond, which himself had built” (Bacon and Lumby 211). Most of his Court was residing there and upon his death ministers went to great lengths (those maneuverings could fill another blog entry) to keep his death secret or at least unannounced, as they worked to decide who should control the realm. Although the transfer of power was not immediate or completely smooth, enough preparations were in place for councilors to solidify their positions and to rally around the 17-year-old Henry VIII, securing the Tudor dynasty. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, assured the kingdom that Henry had handed over the throne to his son by “wisely consyderynge this noble prynce ordred hymselfe therafter, let call for his sone the kynge that now is our governour. He called unto hym and gave hym faderly and godly exhortacion, commyttynge unto him the laborious governaunce of this realme…” (Fisher 285-86).

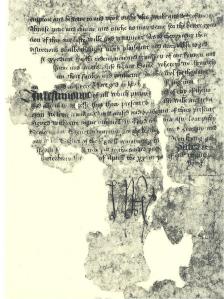

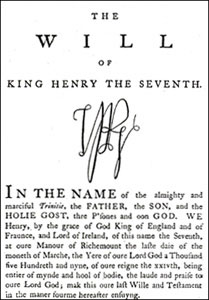

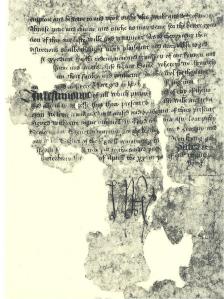

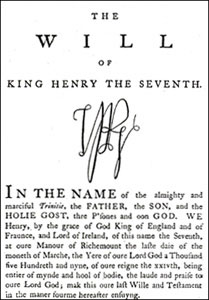

Henry’s will was published, luckily, in 1775 by Thomas Astle as the original is severely damaged. Only a small section of it remains. The will is dated for March 31, 1509, three weeks before the King’s death. Scholars are sure that the will was written in real-time as the place, location and the date were written continuously with the main body of the text indicating that they were not placed in separately (Condon 107).

Fragment of the Will of Henry VII

Published in 1775 by Thomas Astle

The document “captures the king’s authentic voice” and the overall tone is one of contrition and remorse” (Condon 103). Henry VII greatly repented during his final days. Some observers wondered if he felt remorse at the stringent economic measures that were instituted during his rule. Henry requested that his Executors listen to complaints “And in caas by suche examinacion it can be founde, that the complaint be made of a grounded cause … we wol then that as the caas shall require, he and thei bee restored and recompensed by our said Executours, of such our redy money and juelx as then shall remayne…” (Henry VII 12). Here was a man conscious of the financial hardships he imposed on many of his subjects.

Perhaps, as his life drew to a close, he realized money was not the answer to all life’s questions or he was fearful of eternal punishment. Whichever reason, he wanted to ensure that “also if any psone of what degree foevir he bee, shewe by way of complainte to our Executours, any wrong to have been doon to hym, by us, oure commaundement, occasion or meane, or that we helde any goodes or lands which of right ought to apperteigne unto hym; we wol that every such complainte, be spedely, tenderly and effectually herde, and the matier duely and indifferently examyned…” (Henry VII 11).

Besides the King’s preoccupation with righting possible wrongs, the other main provisions of his will were to complete the Lady Chapel, build the Savoy hospital and complete King’s College, Cambridge. Added were the stipulation for alms to be given between the time of his death and burial…” (Condon 104). Contemporaries believed that he was “a great almsgiver in secret; which shewed, that his works in public were dedicated rather to God’s glory than his own” (Bacon and Lumby 212). Furthermore, he gained praise for granting a general pardon for less Earthly rewards “expecting a second coronation in a better kingdom” (Bacon and Lumby 211). To ensure he covered all his bases, Henry stipulated for a “continual and continued edifice of prayer” for his soul (Condon 104).

Illustrated document (and enlargement) of Henry VII requesting prayers and giving alms for the Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey

Edward Hall was confident that, because of Henry’s “noble acts and prudent policies”, when he died “he has the sure fruition of the godhead, and the joy that is prepared for such as shall sit on the right hand of our savior, for ever world without end” (Loades 97). Although as previously mentioned, Henry appeared repentant, perhaps he was fearful of final judgment for evidence of his religious devotion in his final days included hearing several Masses a day and taking the sacrament when “he was of that feblenes that he might not receive it again”, saying confession and kissing the crucifix “not the selfe place where the blessed body of our lorde was conteyned, but the lowest parte of the fote of the monstraunt, that all that stode aboute hym scarsly might conteyn them from teres and wepyng” (Fisher 274).

Henry’s concern was reflected in the Reverend John Fisher’s funeral sermon in which he claimed that, while awaiting his death, Henry “was not without drede” in the face of God’s judgment even though he received “sacraments of crystes chyrche whiche with full grete devocyon…” (Fisher 277).

Bishop of Rochester, John Fisher

After his death 22 April, the ex-king’s body was laid in state at Richmond until 9 May when it was taken by barge as far as London Bridge. From here the casket was processed, in a carriage drawn by horses draped in black velvet, to St. Paul’s Cathedral on 10 May. Atop the coffin was a life-sized effigy worked from Henry’s death mask and draped in parliamentary robes with the scepter and orb. Heraldic banners and flags displaying Henry’s titles and dominions decorated the hearse and route. Inside St. Paul’s, the coffin was laid at the high altar where a Mass for the dead was sung and a vigil kept throughout the night. The funeral service was held on 11 May with the sermon given by Bishop Fisher. Margaret Beaufort, Henry’s mother, was so pleased with the sermon she ordered it to be printed and distributed around the country.

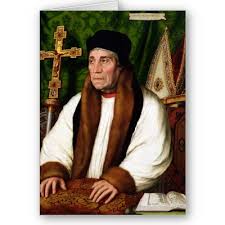

From St. Paul’s the body was again taken in procession, this time to Westminster Abbey for burial to join Queen Elizabeth of York who was already laid to rest there. Several more Masses were sung with the requiem led by Archbishop of Canterbury William Warham. Once the services were completed, the body was interred at Henry’s stipulation “in the Chapell where our said graunt Dame laye buried, the which Chapell we have begoune to buylde of newe, in the honour of our blessed Lady” (Henry VII 4). The ex-king’s household officers broke their staves of office and threw them in the tomb before it was sealed.

William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury

Posthumous reflections stressed the final days of Henry’s life when he showed remorse for some of his administrative policies. Bishop Fisher revealed that worldly pleasures brought Henry unease that “al his goodly houses so rychely dekte & appareyled, his walles & galaryes of grete pleasure, his gardyns large … were paynfull to hym” (Fisher 278). Not to be outdone, Bacon let us know that he was “born at Pembroke castle, and lieth buried at Westminster, in one of the stateliest and daintiest monuments of Europe, both for the chapel, and for the sepulcher. So that he dwelleth more richly dead, in the monument of his tomb, than he did alive in Richmond, or any of his palaces” (Bacon and Lumby 221).

Richmond Palace 1562

Founding the Lady Chapel had been an ambition of Henry VII for some time. His last will and testament is the central text for the creation of the Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey (what is now referred to as Henry VII Chapel). For a detailed explanation of the creation and building of the chapel please refer to the text, Westminster Abbey: The Lady Chapel of Henry VII edited by T. W. T. Tatton-Brown and Richard Mortimer.

Exterior of the Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey, known as the Henry VII Chapel

From the onset, there was going to be no doubt who was the benefactor of the building of the Chapel; starting at the gates the King’s arms, badges, emblems would be shown and repeated throughout the chapel (Condon 64). Pietro Torrigiano was commissioned in 1512 to create Henry VII’s tomb. Seven years later the chapel was completed.

Fan-vaulted ceiling of the Henry VII Chapel

His tomb was in the place of honor as his will decreed “And we wol that our Towmbe bee in the myddes of the same Chapell, before the High Aultier…” (Henry VII 4). Yet, despite imploring his Executors to “full and entrie perfourmyng and executing of this our present Wille, and every thing conteyned in the same,” the tomb was moved to the side (Henry VII 27). Henry VIII moved it behind the altar, “reserving the more prominent space for his own tomb…” (Penn 377).

Tomb of Henry VII & Elizabeth of York, placed behind the altar rather than in the middle to allow space for the monument of Henry VIII

As things in life do happen, Henry VII’s son was not buried at Westminster in the carefully planned testimonial to the Tudor dynasty but his granddaughter, Elizabeth Regina, famously was.

Like her grandfather, Elizabeth grew depressed after the deaths of several people close to her: the Earl of Essex’s execution was a severe blow; the deaths of several of her women, Lady Peyton, Lady Skolt, Lady Heyward and in late February 1603 her cousin Katherine, Countess of Nottingham, granddaughter of her aunt Mary Boleyn and one of her closest attendants.

Katherine Carey Howard, Countess of Nottingham

Her melancholy increased causing attendants (and later historians) to speculate upon the continual causes. Was it the political losses in Ireland? Was it the neglect of Courtiers who were lined up to offer services to James VI of Scotland? Was it the physical ailments which curtailed her activities such as riding and hunting? Was it the deaths of many from her council members? Was it the care and worry of the kingdom? Was it insomnia?

Allegorical painting of Elizabeth I done after 1620 during a revival of interest in her reign

Elizabeth had caught cold in early January which had turned to bronchitis. On January 21 the Court moved to Richmond. The records we have from this time period are pretty extensive from contemporaries’ writings. William Camden was given the Queen’s Rolls, Memorials and Records by William Cecil to use in compiling an historical account of the reign of Queen Elizabeth. He wanted to do her justice, he wanted to obey Cecil and he wanted to tell the truth as he attested on the third page of ‘The Author to the Reader’ note. A noble ambition and one that is hard to argue against. We have from him that in the beginning of Elizabeth’s illness the “Almonds in her Throat swelled, and soon abated again; then her Appetite failed by degrees; and withal she gave herself over wholly to Melancholy, and seemed to be much troubled with a peculiar Grief for some Reason or other” (Camden 659).

William Camden

Her godson, John Harington, tried to cheer her up with verses and light-hearted talk but, according to a letter he sent his wife, Elizabeth told him, “When thou dost feel creeping Time at thy gate, these fooleries will please thee less; I am past my relish for such matters; thou seest my bodily meet doth not suit me well; I have eaten but one ill-tasted cake since yesternight” (Sitwell 453).

John Harington

Her kinsman, Robert Carey, the son of her cousin Lord Hunsdon, also visited her at Richmond and he found her “in one of her withdrawing chambers, sitting low upon her cushions. After greetings he wished her in health and she said ‘No, Robin, I am not well’; and then discoursed with me of the indisposition; and that her heart had been sad and heavy for ten or twelve days; and in her discourse she fetched not so few as forty or fifty great sighs. I was grieved at the first to see her in this plight; for in all my lifetime I never knew her to fetch a sigh, but when the Queen of Scots was beheaded” (Carey 116). Carey continued that “I used the best words I could to persuade her from this melancholy humour but I found by her it was too deep rooted in her heart and hardly to be removed” (Aikin 523).

Robert Carey, surrounded by his wife and children

Carey reported that in late-March on a Sunday Elizabeth had expressed her wish to go to chapel in her closet but she could not make it. Cushions were laid for her on the floor near the closet door and she listened to services from there. “From that day forward she grew worse and worse. She remained upon her cushions four days and nights at the least. All about her could not persuade her either to take any sustenance or go to bed….” (Carey 119). Her coronation ring had to be cut off of her finger as it had grown into the flesh—perhaps hard for her to accept as she had always prided herself in her long, tapered fingers. The removal of the ring “was taken as a sad Omen, as if it portended that her Marriage with the Kingdome, contracted by the Ring, would now be dissolved” (Camden 659).

Some reported that she was losing her mental faculties but John Nichols assured that “there was no such matter; only she held an obstinate silence for the most part, because she had a persuasion, that if she once lay down she should never rise; could not be got to go to bed in a whole week” (Nichols 604). She did not speak for several days “sitting sometimes with hir eye fixed upon one object many howres together, yet shee always had hir perfect senses and memory” (Manningham 146).

Final days of Elizabeth 1 by Paul Delaroch, 1828

The Queen would take no medicines, but she would not go to bed to die either. Maybe we could say it was another example of her trying to see both sides of an issue, trying to compromise, or simply trying to wait-out the events.

The Lord Admiral Charles Howard, Earl of Nottingham, was brought in to persuade her to go to bed. He was successful yet all knew “there was no hope of her recovery, because she refused all remedies” (Aikin 524). Not long after, she had herself pulled to her feet and stood for 15 hours before returning to her cushions. Elizabeth was fighting death with her usual tenacity.

Lord Admiral Charles Howard, Earl of Nottingham

The Venetian Ambassador, Giovanni Scaramelli said she had rallied a little 21 March. Most speculate it was after the abscess in her throat burst allowing for her to feel better for a while. Around this time there occurred the famous incident involving Robert Cecil. He approached the Queen and said “Madam, to content the people you must go to bed” and the Queen rebuked him with “Little man, little man, the word must is not to be used to princes” (Perry The Word of a Prince 317).

Robert Cecil

Carey provided that “on Wednesday the 23rd of March she grew speechless” (Aikin 524). John Manningham, a diarist and lawyer, went to Richmond Palace on that date after the rumors of Elizabeth’s health had reached London and even stories that she was already dead. He was acquainted with Dr. Henry Parry, Bishop of Gloucester and Elizabeth’s favorite chaplain. Manningham dined in the privy chamber with Dr. Parry and several others learning about the Queen’s illness how “for a fortnight she had been overwhelmed with melancholy, sitting for hours with eyes fixed upon one object, unable to sleep, refusing food and medicine, and …still retained her faculties and memory” (Manningham 14).

Henry Parry, Chaplain to Elizabeth Regina

When it appeared as if there would be no recovery, the councilors became anxious to officially secure the succession. Therefore, when she was asked if James VI of Scotland would be her heir, she made a gesture that was taken as assent. Many witnesses relayed with drama that she placed her hands above her head in the shape of a crown, others that she merely motioned with her hand agreement. Regardless of the true action, the movement was taken as her sanction and preparations were made for the ascension of James Stuart. Unlike her grandfather, she left no will. Her treasury was intact and her possessions available for James to inherit as he would her throne.

During her final days Dr. Parry, her chaplain, administered to her when she “tooke great delight in hearing prayers, would often at the name of Jesus lift up hir hands and eyes to Heaven” (Manningham 146).

The Archbishop of Canterbury, John Whitgift, came at about six in the evening of the 23March to pray with her. He knelt at Elizabeth’s bedside and prayed until he became sore and tired and when he “blessed her, and meant to rise and leave her” she gave indication that she wanted him to continue. He did so with “earnest cries to God for her soul’s health, which he uttered with that fervency of spirit, as the Queen to all our sight much rejoiced thereat, and gave testimony to us all of her Christian and comfortable end” (Carey 122). The Archbishop stayed quite late until everyone but a few of her women and, according to some reports, Dr. Parry departed.

John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury

She died between two and three in the morning of Thursday March 24, 1603. Manningham recorded Dr. Parry’s words when he made the death announcement. “This morning about three at clocke, hir Majestie departed this lyfe, mildly like a lambe, easily like a ripe apple from the tree”(Manningham 146). He continued that Dr. Parry reported he “sent his prayers before hir soule” … and concluded that he, Manningham, “doubt not but shee is amongst the royall saints in Heaven in enternall joyes” (Manningham 147).

Upon her death, Elizabeth’s body was tended at Richmond Palace by her ladies, specifically Anne Russell, Countess of Warwick, and Helena Snakenborg, Marchioness of Northampton. Five days later, at night, it was taken along the river in a black-draped barge to Whitehall. There it lay in State in a withdrawing chamber attended continuously by lords and ladies of the Court. Many days later, the body was moved to Westminster Hall to await the King’s orders for the funeral.

Anne Russell, Helena Snakenborg

Countess of Warwick Marchioness of Northampton

The funeral was held 28 April 1603. Elizabeth’s body was processed to Westminster Abbey. Four horses, hung in black velvet, pulled a hearse carrying the coffin which was covered in purple velvet upon which lay the life-sized wax effigy—remade in 1760. Although spectacularly covered in Parliamentary robes, holding the scepter and orb, no hint of Elizabeth’s carefully controlled image of Gloriana remained in the true-to-life likeness from the death mask. When the effigy was seen by the tens of thousands of people along the procession route, it was responded to as emotionally as if it were the Queen in life. John Stowe who attended the funeral left this description of “all sorts of people in their streets, houses, windows, leads and gutters, that came to see the obsequy, and when they beheld her statue lying upon the coffin, there was such a general sighing, groaning and weeping as the like hath not been seen or known in the memory of man” (“History”). Even Scaramelli, the Venetian Ambassador thought the effigy was depicted “so faithfully she semmes alive” (Doran 249).

Funeral procession of Elizabeth Regina, first pictorial record of a funeral of an English monarch

The funeral was organized by Robert Cecil with an estimated cost ranging between £11,305 to £25,000 (in 2010 values that would be £30,800,000 to £68,100,000*) a remarkable sum (Doran 248-249).

The impressive procession of nobles (six earls in no less, in mourning dress, supported the canopy of estate under which was the coffin) with councilors, clerics, courtiers, heralds, gentlemen, servants and 276 poor people filed behind. Over a thousand people took their place with the peeresses of the realm, who were led by the chief mourner the Marchioness of Northampton. Archbishop Whitgift officiated at the service which saw the interment of Elizabeth under the main altar of the chapel of her grandfather, Henry VII. Following tradition her officers broke their staves and threw them atop the coffin before the tomb was sealed.

Three years later, Elizabeth’s body was relocated, along with her sister Mary’s to a chapel James I had created on the north aisle. This blogger had contacted Westminster Abbey to confirm via primary source evidence that Elizabeth was first buried in Henry VII’s tomb. Miss Christine Reynolds, Assistant Keeper of Muniments, verified that there is a document in the Abbey archives, reference W. A. M. 33659 of 1605-06, that authorized the removal of the Queen’s body from Henry VII’s vault to the present tomb. The effigy of the newer monument was sculptured by Maximilian Colt and painted by John de Critz according to some reports it too was worked from the death mask at a cost of £1485 (£4,040,000 in 2010 values*).

Tomb of Elizabeth Regina

The Latin inscription on her tomb would have pleased her. Below is a portion of it translated:

“Mother of her country, a nursing-mother to religion and all liberal sciences, skilled in many languages, adorned with excellent endowments both of body and mind, and excellent for princely virtues beyond her sex” (“History”).

Monument to Elizabeth I in Westminster Abbey

Elizabeth had gained the love and devotion of her people and had ruled with great popularity. William Camden’s biography was to prove prophetic when he said: “No Oblivion shall ever bury the Glory of her Name: for her happy and renowned Memory still liveth, and shall for ever live in the Minds of men to all Posterity” (Camden 661).

Once the proclamation was made for James I, the crowds were not exuberant as “sorrowe for hir Majesties departure was soe deep in many hearts they could not soe suddenly showe anie great joy” (Manningham 147).

That sorrow manifested itself 10 years later in comments made by Edward Hall. “Such was the sweetness of her government and such the fear of misery in her loss, that many worthy Christians desired that their eyes be closed before hers” (Aikin 529).

It was the “new men and new manners brought in by James I served to teach the nation more highly to appreciate all that it had enjoyed under his illustrious predecessor…” and the “despicable weakness of her successor caused her decease to be regretted and deplored” (Aikin 529).

Many people saw the significance of her death date with William Camdon explaining: “On the 24 of March, being the Eve of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin, she (who was born on the Eve of the Nativity of the same Blessed Virgin) was called out of the Prison of her earthly Body to enjoy an everlasting Country in Heaven, peaceably and quietly leaving this Life after that happy manner of Departure… having reigned 44 Years, 4 Months, and in the seventieth Year of her Age; to which no King of England ever attained before” (Camdon 661).

Stanza 21 and 22 of a poem written by Queen Elizabeth

Regret for my fault

Delivered me from sin,

For it afflicted me so

That this alone was my care—

That I did not have care enough;

Knowing better, that in joy

I had to suffer,

I turned myself to so many tears

That a thousand times my comfort

Renewed my pains.

To increase the grief

Of my follish past,

Contemplating my Creator,

I remember the making

Of me, a sad sinner;

I saw that God redeemed me,

Beign cruel against Him,

And considering well who He was,

I saw how He made Himself me,

So that I would make myself Him.

Queen Elizabeth (Marcus 419)

*Values for pounds were figured using the Measuring Worth website at http://www.measuringworth.com/ppoweruk/

References

Aikin, Lucy. Memoirs of the Court of Elizabeth, Queen of England. London: G. P. Putnam, 1870. Kindle.

Bergenroth, G. A., and, Pascual De. Gayangos. Calendar of Letters, Dispatches and State Papers, Relating to the Negotiations between England and Spain, Preserved in the Archives at Simancas and Elsewhere: Published by the Authority of the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury under the Direction of the Master of the Rolls. Henry VII 1485 – 1509. ed. Vol. 1. London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1862. Google Books. Web. 26 Nov. 2012.

Borman, Tracy. Elizabeth’s Women: The Hidden Story of the Virgin Queen. London: Jonathan Cape. 2009. Print.

Camden, William, and Robert Norton. Annals, Or, The Historie of the Most Renovvned and Victorious Princesse Elizabeth, Late Queen of England.: Containing All the Important and Remarkable Passages of State, Both at Home and Abroad, during Her Long and Prosperous Reigne. 4th ed. London: Printed by Thomas Harper, for Benjamin Fisher, and Are to Be Sold at His Shop in Aldersgate Street, at the Signe of the Talbot., 1688. Google Books. Web. 2 Dec. 2012.

Carey, Robert Sir, Earl of Monmouth. The Memoirs of Sir Robert Carey. Edinburgh: James Ballantyne and Co. and Archibald Constable and Co.. 1808. Google Books. Web. 15 Apr. 2013

Condon, Margaret. Westminster Abbey: The Lady Chapel of Henry VII. Ed. T. W. T. Tatton-Brown and Richard Mortimer. Rochester, NY: Boydell, 2003. Google Books. Web. 14 Apr. 2013.

Doran, Susan, ed. Elizabeth: The Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum. London: Chatto & Windus, 2003. Print.

Doran, Susan. The Tudor Chronicles 1485-1603. New York: Metro Books, 2008. Print.

Erickson, Carolly. The First Elizabeth. New York: Summit Books. 1983. Print.

Fisher, John, and John E. B. Mayor. “Sermon Sayd in the Cathderall Chyrche of Saynt Poule within the Cyte of London the Body Being Present of the Moost Famous Prynce Kyng Henry the VIII, 10 May MCCCCCIX. Enprinted by Wynkyn De Worde 1 H. VIII.”The English Works of John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester. London: N. Trübner for the Early English Text Society, 1876. 268-88. Google Books. Web. 1 Dec. 2012.

Frye, Susan. Elizabeth I: The Competition for Representation. Oxford: Oxford Univseity Press. 1993. Print.

Griffiths, Ralph A. and Roger S. Thomas. The Making of the Tudor Dynasty. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985. Print.

Henry VII. The Will of King Henry VII. London: Printed for the Editor: and Sold by T. Payne; and B. White, 1775. Google Books. Web. 13 Apr. 2013.

Hibbert, Christopher. The Virgin Queen: Elizabeth I, Genius of the Golden Age. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1991. Print.

“History.” Elizabeth I. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey, n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2013.

Jones, Michael K. and Malcolm G. Underwood. The King’s Mother: Lady Margaret

Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Print.

Levin, Carole. The Heart and Stomach of a King: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Sex and Power. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 1994. Print.

Loades, David, ed. The Tudor Chronicles: The Kings. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990. Print.

Manningham, John, and John Bruce. Diary of John Manningham of the Middle Temple and of Bradbourne, Kent, Barrister-at-law, 1602-1603. London: Camden Society, 1868. Open Library, 13 Apr. 2010. Web. 2 Dec. 2012.

MacCaffrey, Wallace. Elizabeth I. London: E. Arnold. 1993. Print.

Neale, J. E. Queen Elizabeth I. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1957. Print.

Nichols, John. The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth. Among Which Are Interspersed Other Solemnities, Public Expenditures, and Remarkable Events during the Reign of That Illustrious Princess. Collected from Original MSS., Scarce Pamphlets, Corporation Records, Parochial Registers, &c., &c.: Illustrated with Historical Notes. New York: B. Franklin, 1823. Google Books. Web. 19 Jan. 2013.

Norton, Elizabeth. Margaret Beaufort: Mother of the Tudor Dynasty. Stroud: Amberley, 2010. Print.

Penn, Thomas. Winter King; the Dawn of Tudor England. New York: Penguin Books, 2012. Print.

Perry, Maria. The Sisters of Henry VIII. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. Print.

Perry, Maria. The Word of a Prince: A Life of Elizabeth from Contemporary Documents. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1990. Print.

Ridley, Jasper. Elizabeth I: The Shrewdness of Virtue. New York: Fromm International Publishing Corporation, 1989. Print.

Sitwell, Edith. The Queens and the Hive. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1966. Print.

Somerset, Anne. Elizabeth I. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. Print.

Strachey, Lytton. Elizabeth and Essex: A Tragic History. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1969. Print.

Starkey, David, ed. Rivals in Power. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990. Print.

Weir, Alison. The Life of Elizabeth I. New York: Ballatine Books, 1998. Print.